New Work, Fewer Jobs: Four Forces Behind AI's Creative Destruction

Exploring four forces that drive the expansion of types of work

When DeepSeek announced their cutting-edge AI model at bargain prices, the tech industry panicked. Stock prices tumbled. VCs warned of disruption. But Microsoft's CEO Satya Nadella had a different take: he tweeted about "Jevons paradox," a 160-year-old economic concept.

The term quickly became Silicon Valley's comfort blanket. VCs who had just warned of doom now cited it to justify their AI investments. The Google Trends chart tells the story - a meteoric rise and fall as the industry grasped for simple explanations that would let them keep calm and keep investing on.

I've written about Jevons paradox before - how efficiency gains can paradoxically increase demand rather than reduce it. But watching this concept become a corporate mantra made me wonder: When does this pattern actually hold true? What determines whether efficiency gains create more work or simply eliminate jobs? As I investigated these questions, I encountered four distinct forces that might explain Jevons' insight, and how the universe of work actually expands.

What is Jevons' Paradox?

In 1865, economist William Stanley Jevons noticed something counterintuitive. When steam engines became more efficient, using a third as much coal, coal consumption didn't decrease - it increased. Greater efficiency had lowered costs so much that entirely new uses for steam power became viable. Steam engines moved from factories to mines to railways, each efficiency gain enabling new possibilities rather than reducing demand.

Today's tech industry hopes AI will follow this pattern. We've already seen it with software development - as tools got better and cheaper, our appetite for software didn't decrease, it increased. Basic economics would suggest that when supply increases (through greater efficiency), prices fall and we reach a new equilibrium. But Jevons observed something more interesting: in some cases, demand doesn't just adjust - it expands dramatically.

As I thought about why this happens - why some efficiency gains create explosive growth in demand while others just lead to lower prices - I began to see patterns. There seem to be four distinct forces that might explain this expansion of demand, each playing a different role in how the universe of work evolves.

First, as costs drop dramatically, previously unprofitable niches become viable. Chris Anderson called this the "Long Tail" effect - when digital economics suddenly makes it possible to serve interests that physical businesses never could.

Second, new technologies don't just make existing things cheaper - they enable entirely new possibilities. The smartphone didn't just make phone calls more efficient; it created entirely new categories of work, from app development to ride-sharing.

Third, the power of narrative can transform even basic commodities into entirely new categories. This isn't just about making things cheaper or more efficient - it's about reimagining what they mean.

And finally, there's the ultimate form of narrative: status games. These create an infinite ladder of differentiation, where each level spawns its own ecosystem of work.

Let's explore each of these forces in turn, starting with how the Long Tail effect is reshaping our understanding of viable work.

The Long Tail Effect

When Amazon launched in 1995, traditional bookstores were constrained by shelf space. They could only stock books that would sell enough copies to justify their spot on the shelf. But Amazon's digital shelves were infinite, which meant they could stock every book ever printed. Chris Anderson, writing in Wired magazine, called this the "Long Tail" effect - when digital economics makes it viable to serve niche interests that physical businesses never could.

What's interesting is how this created a virtuous cycle. Amazon didn't just provide shelf space for existing niche books - it created the conditions for more niche books to be written. Authors could now write for highly specific audiences, knowing there was a way for their readers to find them. The long tail didn't just serve existing demand; it enabled new supply.

We're seeing this same pattern accelerate with software development. In the early days, business software had to be broad to justify its development costs. You had general-purpose CRMs trying to serve everyone from enterprise sales to restaurant chains. But as development tools got better and cheaper, something interesting happened: the market started splitting into specialized niches.

Now we have Salesforce optimized for enterprise sales teams, ServiceTitan built specifically for home service businesses, and Toast designed just for restaurants. Each of these specialized tools serves its market better than a general-purpose solution ever could. As development costs dropped, it became viable to build software for increasingly specific use cases.

This isn't just about making existing software cheaper - it's about enabling entirely new categories of software that weren't economical before. When the cost of creation drops low enough, the universe of viable ideas expands dramatically.

The Long Tail effect explains how automation makes more niches viable, but it doesn't explain how entirely new categories of work emerge. For that, we need to look at our second force: technology-enabled possibilities.

Technology-Enabled Possibilities

The smartphone didn't just make phone calls cheaper or more efficient - it created entirely new categories of work that couldn't have existed before. Ride-sharing services like Uber weren't just a more efficient taxi dispatch system. They required a specific combination of technologies: smartphones with GPS, mobile internet, and digital payments. Once these capabilities converged, entirely new business models became possible.

Kevin Kelly, founder of Wired magazine and longtime observer of technological change, writes in "The Inevitable" about how this pattern repeats: first, we have jobs only humans can do, then machines learn to do them, and eventually surpass human capability. But by then, we've discovered entirely new categories of work we never knew we wanted done.

Consider digital photography. When it first emerged, we thought it would just make traditional photography more efficient. Instead, it enabled entirely new forms of visual expression - from Instagram filters to augmented reality to computational photography that can see around corners. Each advance didn't just automate an existing task; it revealed new creative possibilities we couldn't have imagined in the analog era.

But even this doesn't fully explain how new jobs emerge. Sometimes new categories of work appear not because of technological capability, but because of how we reimagine what something means. This brings us to our third force: the power of narrative.

The Power of Narrative

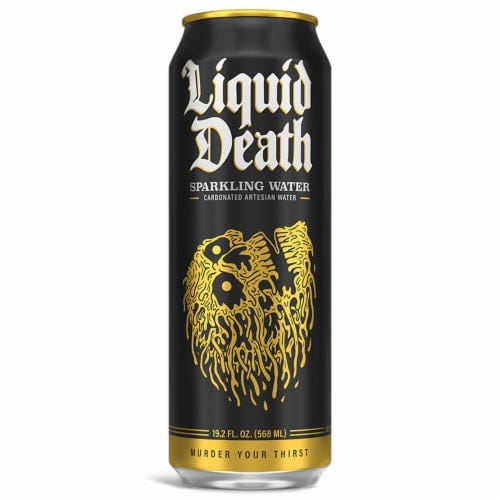

Consider water. It's the ultimate commodity - literally falling from the sky. Traditional economics would suggest there's no room for differentiation or premium pricing. Yet a company called Liquid Death took ordinary canned water and turned it into a cultural phenomenon by reimagining it as a rebellion against both sugary drinks and pretentious water brands. They didn't make water more efficient to produce or distribute. They created an entirely new category by changing what water could mean.

This pattern of narrative transformation becomes even more powerful with technology. Take GoPro. In the early 2000s, portable cameras were commodities. But by reimagining the camera as a tool for sharing epic experiences, GoPro created an entire digital ecosystem of work: professional adventure filmmakers, YouTube athletes, drone operators, and social media content creators, all building careers around capturing and sharing extreme moments. Each successful narrative creates concentric circles of work.

We're seeing this same transformation with AI tools. GitHub Copilot isn't just an efficient code generator - it's being reimagined as a "pair programmer," creating new roles for AI-human collaboration specialists and workflow designers. When Midjourney frames AI art as "imagination infrastructure," it creates space for prompt engineers, style consultants, and AI art curators.

But there's an even more powerful force at work here. Some narratives aren't just about reimagining products - they're about signaling status and differentiation. This brings us to our final force: the status game.

Status: The Ultimate Narrative

I've written before about how status games create infinite cycles of competition, much like the peacock's tail in evolutionary biology. Status might be the most powerful narrative of all because it's inherently relative - it's not enough to be good, you need to be better than your competitors.

Consider Apple's website evolution. In the 1990s, having any website was enough. But as web development tools improved, simply having a website wasn't sufficient. Apple began creating increasingly sophisticated experiences - custom animations, stunning scroll effects, and interactive features that required serious development talent. Each innovation raised the bar, forcing others to follow.

This creates what evolutionary biologists call "runaway selection" - an arms race where each advance triggers the need for further advances. When everyone has access to good design tools, companies hire expensive agencies. When that becomes common, they commission custom artwork. When that becomes standard, they create interactive experiences. There's no endpoint because status isn't about achieving a particular level - it's about proving you can invest more than others.

We're already seeing this pattern emerge with AI. According to Gartner, "By 2026, 80% of advanced creative roles will be tasked with harnessing GenAI to achieve differentiated results." But this won't lead to cost savings. As Gartner analyst Jay Wilson notes, "The use of GenAI in a creative team's routine daily work frees them up to do higher level, more impactful creative ideation, testing, and analysis." The result? CMOs will actually increase their creative spending as teams focus on more sophisticated differentiation.

This is the status game in action. When AI makes basic content creation effortless, the premium shifts to unique perspectives and novel applications. When every website can be beautiful, distinction comes from innovative interactions. When all products can be well-designed, status emerges from ever more subtle forms of differentiation. Like peacocks evolving ever more elaborate tails, we're locked in an endless race to stand out.

New Categories, Fewer Jobs

Throughout this article, we've explored four forces that drive the expansion of work: the long tail effect making new niches viable, technology enabling new possibilities, narratives transforming commodities into categories, and status games creating infinite ladders of differentiation. Each force suggests ways that new categories of work will emerge as AI transforms our economy.

But we should be clear-eyed about what this means. New categories of work don't necessarily translate to more jobs - or even the same number of jobs. We've seen this pattern before. Over the past 30 years, the tech sector has grown from 0.8% to 10% of GDP - a staggering 12,500% increase in economic output. Yet its share of employment has only grown from 2.8% to 7%. While these tech jobs pay 85% more than the average US worker, there are far fewer of them than the jobs they displace.

This is the paradox at the heart of technological progress. The same forces that create new possibilities also concentrate economic value in ways that require fewer workers. Yes, AI will enable new categories of work we can't yet imagine. But if history is any guide, these new categories will likely employ fewer people than the industries they disrupt.

![The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces that Will Shape Our Future [Book] The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces that Will Shape Our Future [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!8vBp!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F618ad58a-59db-412e-b92f-13ff80323e7d_1650x2531.jpeg)