Are We There Yet?: Musings on AI's Endless Road Trip

Why our inability to see AI's destination might be our greatest advantage in shaping its journey.

"Are we there yet?" It's the universal anthem of road trips, the question that echoes from back seats around the world approximately every four minutes. Parents know the familiar mix of amusement and exasperation as they answer "not yet" for the hundredth time, watching their children struggle with the concept of a journey too big for their current understanding.

The AI industry has been living its own version of this endless road trip. Last year, the equation seemed simple: bigger models meant better results. The giants of tech nodded in agreement, each racing to build ever-larger systems. Then Mistral showed up with a 7B model that punched far above its weight class. Next came o1's reasoning capabilities, then DeepSeek R1's efficiency breakthrough - each time we thought we'd cracked the code, only to have our assumptions challenged.

What started as a race for bigger models became a competition for reasoning capabilities, then a quest for efficiency. Each shift brought its own "we've solved it" moment. O1 showed how to break down complex problems step-by-step, costing billions in compute and research. Then DeepSeek R1 achieved similar results for $6 million, forcing us to rethink everything again.

The comments sections light up with questions: "Is Nvidia overvalued?" "Has DeepSeek won?" "Are we finally there?" Each breakthrough becomes another milestone on a journey whose destination keeps shifting. And like those children in the backseat, we're forever wanting the trip to end and declare victory. It's not impatience so much as a deeply human need to feel we've reached our destination.

The End of History Illusion: Our Terrible Track Record of Predicting Change

This need to declare "we're there!" isn't unique to road trips or AI development. It's built into how we think about change itself. In 2013, researchers asked 19,000 people a simple question: how much have you changed in the past decade, and how much will you change in the next? The results showed a clear pattern. At every age, from 18 to 68, people saw significant changes in their past but expected stability in their future. They all thought: "This is who I am now." Psychologist Dan Gilbert and his colleagues named this tendency "the end of history illusion".

Sound familiar? The AI industry keeps having these "now we've figured it out" moments. When large language models first emerged, we thought bigger was always better - that was clearly the path forward. When open source models appeared, we were certain they couldn't compete with the tech giants' massive compute budgets. When reasoning capabilities became the focus, we believed only billion-dollar investments could crack that code.

Each time, we think we've found the key to AI's future, only to have the next breakthrough reveal new horizons. As Gilbert, the psychologist who first identified this pattern, puts it: "Human beings are works in progress that mistakenly think they're finished. The person you are right now is as transient, as fleeting and as temporary as all the people you've ever been."

The Exponential Curve: Why We're Bad at Reading the Road Map

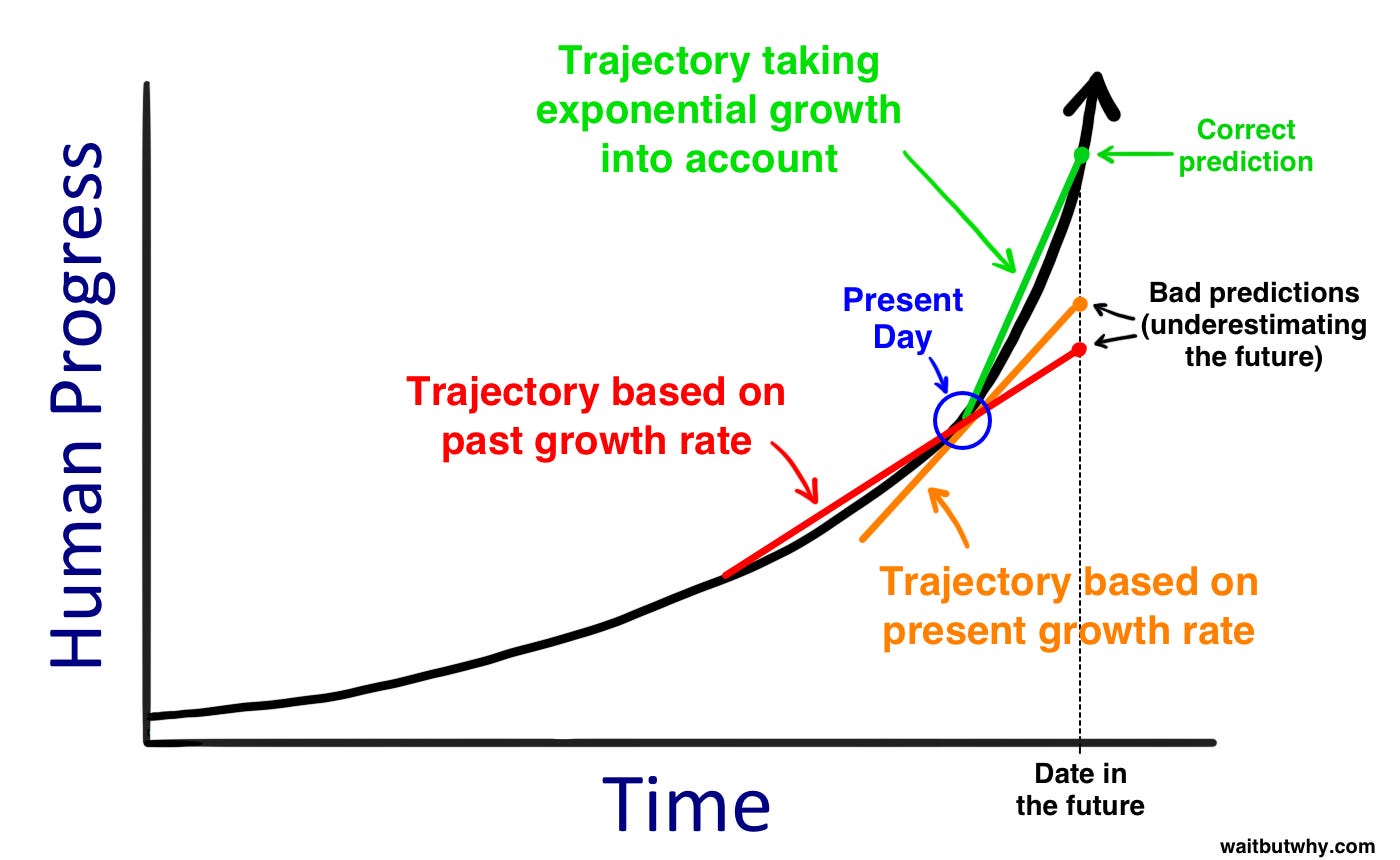

Our struggle with predicting AI's future isn't just about psychology - it's about how our brains process change. As Tim Urban explains in "The AI Revolution", we instinctively think in straight lines. When we try to predict the future, we take the current rate of progress and extend it forward, like drawing a straight line from where we are.

But as the image shows, this linear thinking consistently leads us astray. Technology doesn't advance in straight lines - it accelerates, each breakthrough building on previous ones to create exponential growth. We're standing at that blue dot marked "Present Day," trying to guess what comes next. And we keep getting it wrong because we can't intuitively grasp the curve's true trajectory.

But here's the thing: maybe we don't need to. Anne Lamott shares an insight that cuts to the heart of how we navigate uncertainty:

E. L. Doctorow once said that "writing a novel is like driving a car at night. You can see only as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way." You don't have to see where you're going, you don't have to see your destination or everything you will pass along the way. You just have to see two or three feet ahead of you. This is right up there with the best advice about writing, or life, I have ever heard.

This is how humanity has always navigated exponential change. The farmers of 1800 couldn't have imagined their great-grandchildren working in skyscrapers. The first computer programmers couldn't have pictured smartphones. But that didn't stop us from building those futures, one step at a time, guided only by what was in our headlights.

The end of history illusion tells us we're bad at imagining change. The math of exponential growth tells us we're bad at predicting it. But our track record tells us something more important: we don't have to be good at either. We just have to keep solving what's in front of us, keep following the road as far as we can see it. That's how we've made every great transition in human history, and it's how we'll make this one too.

The Road Goes On: Learning from Past Revolutions

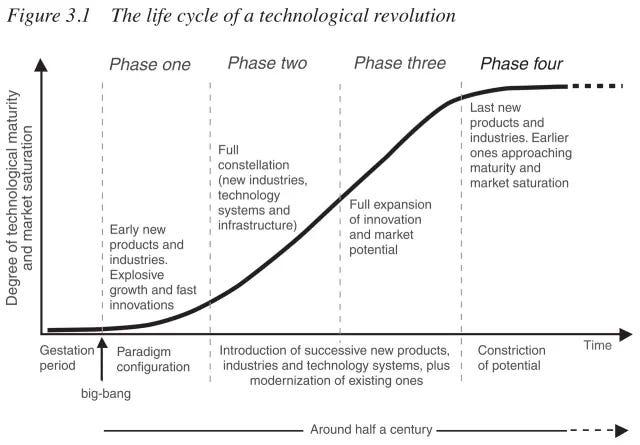

Carlota Perez, an economic historian at the London School of Economics, mapped the patterns of five major technological revolutions, from the Industrial Revolution to the Age of Information. Her research shows how each revolution follows similar phases of development and adoption. Each started with what she calls a "big bang" - from Arkwright's mill in 1771 to the Intel microprocessor in 1971. Each triggered its own version of "are we there yet?" And each time, what looked like the destination turned out to be just the beginning.

Take electricity. It started with lighting - Edison's bulb solving a specific, limited problem. But that was just the first step. Electric motors transformed manufacturing. Assembly lines reshaped production. New industries emerged that Edison never imagined. Each "we're there" moment became a stepping stone to something bigger.

The Shape of Change

Perez's research reveals a consistent pattern in how these technologies develop. First comes gestation - the early technical experiments. Then paradigm configuration, when the basic rules of the technology become clear. Next is the infrastructure phase, when supporting systems develop. Market expansion follows as applications multiply. Finally comes maturity - not an endpoint, but a plateau from which new possibilities emerge.

AI is following this pattern. We started with narrow tasks like game-playing and image recognition. Large language models emerged, triggering the first "we've solved it" moments. Then came the efficiency breakthrough - Mistral showing that small models could match their larger cousins. Now we're seeing new capabilities in reasoning and problem-solving. What started as token prediction became few-shot learning, then chain-of-thought reasoning, then tool use - each capability unlocking new horizons we hadn't imagined.

The questions we're asking now - Will open source or closed systems dominate? Is compute or efficiency the key factor? What's the right balance between capability and cost? - these aren't signs that we're lost. They're markers of the paradigm configuration phase. Just as the early electrical industry debated AC versus DC, standardized voltages, and distribution systems, we're working out the fundamental rules of AI development.

The View from Here

The pattern is clear: there is no "there." The Intel 4004 microprocessor wasn't the destination of the computer revolution - it enabled personal computers, which enabled the internet, which enabled mobile computing, "we're there" moment was actually an opening to new technical possibilities.

The end of history illusion isn't just a psychological quirk - it's how we manage complex technological change. We focus on immediate technical challenges: making models more efficient, improving reasoning capabilities, reducing training costs. Each solution becomes a platform for new questions, new possibilities, new technical horizons.

Those headlights showing just the next few feet of road? They're not a limitation - they're a proven methodology. Edison didn't need to envision modern electronics to create the light bulb. The Wright brothers didn't need to imagine jumbo jets to solve powered flight. And we don't need to see AGI or ASI to make meaningful progress in AI development.

The real question isn't "are we there yet?" There is no there. The question is: what technical possibilities will today's solutions unlock? What new capabilities will emerge from our current work on efficiency and reasoning? We're not lost children in the backseat - we're building the road as we drive, each solution creating new paths forward.

But.. Are we there yet?

Related: