Why AI Doesn’t Need to Work Perfectly to Win

The lesson from 1929: When technology unlocks impossible capabilities, adoption doesn’t wait for reliability—it happens when something impossible becomes merely unreliable.

An article titled “AI Agents can’t schedule meetings but promise to replace workers” has been making the rounds recently. In it, the author claims GPT-4o failed most basic office tasks in their test. And sixteen years and billions of dollars later, self-driving cars operate in a handful of cities under limited conditions.

The takeaway: AI agents can’t schedule meetings how will they take away jobs? There are many forms of this reliability argument I see floating around.

The numbers are sound and the logic feels air-tight.

But something about the argument feels off.

The reliability critique assumes technology succeeds by being better at existing tasks. If it can’t match or exceed current reliability standards, it’s not ready for adoption.

This seems obvious. But it’s not the whole story.

To understand why, we need to look at how technology actually gets adopted—not how we think it should.

Early technology is never as reliable as what it replaces. But that’s not the barrier to adoption we think it is. When something unlocks a capability that didn’t exist before, reliability becomes secondary. Sometimes a 30% success rate at something we couldn’t do before matters more than a 99% success rate at something that we already do. Innovation scholars from Everett Rogers to Clayton Christensen have documented this pattern: early technologies rarely win by outperforming incumbents—they win by redefining what “performance” means. History has many stories about this pattern, let’s look at a couple.

Fast But Fragile Beats Slow But Safe

In 1929, if you needed to send an urgent contract from New York to San Francisco, you had one option that worked: the railroad. Your letter would travel in a mail car, sorted and handled by postal workers who had refined their systems over decades. The journey took five days. But it worked. Mail arrived reliably, predictably, intact. The railroad companies had spent half a century perfecting this system.

Then the airmail service launched.

The first planes were modified military aircraft left over from World War I. They were temperamental machines that required constant maintenance. Weather grounded them regularly. Mechanical failures were common. And sometimes, they crashed.

According to USPS historical archives, in 1929 alone, fifty-one airmail planes went down. Nearly three dozen pilots had died in the previous decade trying to deliver mail by air. If you sent your urgent contract by airmail, you faced a chance your letter would burn up in a crash somewhere over the heartland.

The flying conditions were brutal. Pilots flew exposed biplanes left over from World War I—not fully enclosed cockpits, just open to cold rain and wind. Hot engine oil constantly splattered their goggles. They flew barely 50 feet off the ground so they could see railroad stations and polo fields to stay on course. One pilot who flew the demonstration route in 1921 drank coffee and stuffed newspaper in his jacket for warmth before continuing through near-crashes in the dark.

Business leaders knew these numbers. The contrast was stark: trains had crossed the continent reliably for half a century. The railroad system worked. Why would anyone risk an important document on such dangerous technology?

Yet businesses kept paying premium prices to send their most important documents by air.

The math was simple. Trains took 108 hours coast-to-coast. Airmail took 33 hours. For time-sensitive documents, one day of delivery at 70% reliability beat four-and-a-half days at 99% reliability. A contract that arrived in one day could close a deal before competitors even knew about it. A legal filing that arrived in one day could meet a deadline that four days would miss.

Speed had unlocked a capability that didn’t exist before. And that new capability was valuable enough to tolerate unreliability.

When Something Beats Nothing

The business world was unconvinced. As late as 1879, the Chief Engineer of the British Post Office declared that “The Americans have need of the telephone, but we do not. We have plenty of messenger boys.” The telegraph system worked reliably, with clear printed messages that left no room for mishearing or misunderstanding.

But the skeptics weren’t wrong about the telephone’s shortcomings.

Early telephone users described the experience as one of “feebleness and uncertainty.” The carbon granule microphones created scratchy, harsh sounds. Interference from nearby telegraph wires and electrical currents would nearly drown out the speaker’s voice. Weather created static. Long distances created echo. Call quality was so poor that one 1880 testimonial warned potential users: “strangers hearing through it for the first time may find themselves on that account disappointed.”

But telegraph service worked perfectly. Messages arrived intact, properly formatted, readable. You could send a telegram at 2 AM and know it would be delivered first thing in the morning. The system had been refined over decades. Why would anyone switch to a technology where you had to shout “Hello? Hello?” multiple times just to establish that someone was on the other end?

Yet within two years of Bell’s patent, the first commercial telephone exchange opened in New Haven, Connecticut with 21 subscribers. By 1880, Ithaca, New York had 100 telephone subscribers—described as “a larger number than has been obtained in so short a time in places even of twice the size.”

The telegraph could do many things better than the telephone. But it couldn’t do one thing at all: real-time back-and-forth conversation.

If you needed to negotiate a deal, telegraph required sending a message, waiting for a response, sending another message, waiting again. Each round trip took hours. A simple negotiation could stretch over days. The telephone, even with its terrible audio quality, let you have that entire conversation in minutes. You could hear hesitation in someone’s voice. You could clarify misunderstandings immediately. You could close deals while your competitors were still composing their first telegram.

The dimension that mattered wasn’t audio fidelity. It was synchronicity. And synchronous voice communication at 30% reliability beat asynchronous text communication at 99% reliability for any task that required real-time interaction.

The Pattern Continues

This same dynamic plays out today, though we often miss it while focusing on reliability metrics.

I tried Apple’s new Live Translation feature last month. You press both AirPod stems simultaneously and it activates real-time translation for in-person conversations. The feature launched in September 2025 with support for nine languages, processing everything on-device for privacy.

It’s laggy. The translations arrive a half-second behind the speaker, creating this awkward pause in conversation. Sometimes it misses words entirely. The accuracy isn’t perfect—nuance gets lost, idioms get mangled. If you tried to conduct diplomatic negotiations or close a complex business deal through it, you’d probably fail.

But here’s what it does do: it lets you have a conversation with someone whose language you don’t speak. Not a polished, perfectly understood conversation. A halting, imperfect, occasionally confusing conversation. But a conversation nonetheless.

Before this technology, what were your options? Hand signals. Translation apps where you type, wait, show your phone, wait for them to type, show their phone back. Maybe a professional translator if you planned ahead and could afford it. For spontaneous interactions—asking directions, ordering food, having an unplanned conversation with a neighbor—you had nothing.

The AirPods translation feature isn’t replacing professional translators. It’s not good enough for important negotiations or medical consultations. But for the thousands of small interactions where the alternative was frustration and miscommunication? Even at 70% accuracy with noticeable lag, it beats 0% capability.

The reliability critics would point out—correctly—that it fails too often for serious use. But they’re measuring the wrong dimension. The question isn’t “Is it as reliable as a professional translator?” The question is “Does it unlock conversations that couldn’t happen before?”

Same pattern as airmail. Same pattern as the telephone. Technology doesn’t win by being more reliable than existing solutions. It wins by making things possible.

The Question That Matters

The reliability critics are right about the numbers. AI agents do fail basic tasks. Self-driving cars do require perfect conditions.

But that’s not the question that determines adoption.

The question is: what dimension does AI unlock that didn’t exist before?

The pattern from 1929 still holds: when technology unlocks an impossible dimension, we tolerate unreliability. When it only promises to do existing tasks better, reliability matters enormously. For safety-critical systems—medical devices, aviation, autonomous vehicles—the bar is appropriately high. But even there, driver assistance features arrive before full autonomy, providing new capabilities while the technology improves.

So the next time someone shows you statistics about AI failure rates, ask yourself: what dimension is this trying to unlock? If it’s trying to replace something that already works, the reliability bar is high. But if it’s trying to make something possible that wasn’t before—even with significant failures—the math might work out differently than the skeptics think.

The future of AI may not look like perfect autonomous systems replacing human workers. It will look like imperfect tools unlocking capabilities we didn’t have, with humans adapting their workflows around what the technology can actually do. Just like businesses in 1929 learned to send documents both by air and train. Just like early telephone users learned to shout “Hello?” until someone answered.

Reliability will improve over time. But adoption doesn’t wait for reliability. It happens when something impossible becomes merely unreliable. And right now, AI is making a lot of impossible things merely unreliable. Real-time language translation, code generation, content creation, complex analysis—tasks that previously required specialized expertise or were simply too resource-intensive to attempt. We tolerate their unreliability because the alternative was having no capability at all.

The railroad worked perfectly too. That’s not what mattered.

Related:

The Rollercoaster Ride of AI: Hype, Hope, and Reality

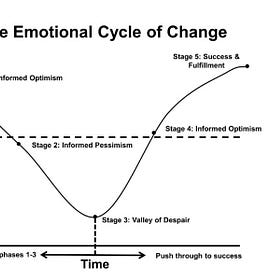

Change is messy. When companies roll out major new initiatives like reorganizations, IT system changes, or process redesigns, employees get swept away on an emotional rollercoaster ride. In the 1970s, psychologists Don Kelley and Daryl Conner coined this bumpy track, the

Everyday Magic: How Groundbreaking Technology Becomes Commonplace

As a startup founder, two quotes have deeply influenced my perspective on technology and innovation. The first comes from sci-fi writer Arthur C. Clarke: