When AI Becomes Plumbing

How AI moves from product to infrastructure

What does it mean to use AI today?

You open a browser tab. ChatGPT. Claude. Maybe Gemini. You type a question, get an answer, close the tab. That’s AI. It’s an app. A website. A thing you do.

Meanwhile, your computer has no idea any of this happened. Your calendar doesn’t know. Your email client doesn’t know. AI lives in a browser tab, isolated from everything else on your machine.

We’ve been here before.

When the Network Was Elsewhere

In 1994, you could go online. You’d launch AOL or CompuServe, hear the modem screech and hiss—two machines negotiating in audible data—and suddenly you were somewhere else. Science fiction had taught us to call it cyberspace: a neon-lit elsewhere you jacked into. You’d check email, browse content, maybe enter a chat room. Then you’d disconnect and your computer would be offline again.

The network was a place you visited. Your computer didn’t live there.

Windows 3.1 didn’t know what TCP/IP was. If you wanted your computer to actually speak the language of the internet, you needed third-party software like Trumpet Winsock—a $30 shareware stack that required manual configuration. It was like teaching your computer a foreign language it was never designed to speak.

This wasn’t just inconvenient. It was architectural. Your spreadsheet couldn’t fetch data. Your calendar had no idea the network existed. If you wanted information from the internet in another program, you were the messenger: copy from AOL, paste into Word, write down the weather forecast, manually add the phone number to your contact book.

Networking was something you made your computer do, temporarily, by launching special software and shepherding data between worlds. Sound familiar?

When Your Computer Joined the Network

In August 1995, Windows 95 shipped with TCP/IP built in. The operating system could finally speak the language of the internet natively. And once it wasn’t something you did but something your computer was—the world changed.

Because things started happening without you.

You’re asleep. Your computer isn’t. At 3am it checks a server in Redmond, downloads a security patch, installs it, restarts a background process. You never know this happened. You never needed to know. Before, updating software meant, ordering a floppy disk, waiting for it to arrive, running the installer. Now software just... stayed current. Your computer reached out and fixed itself.

Your calendar receives an email with meeting details. It parses the date, the time, the location, checks for conflicts, adds the event, sets a reminder, syncs to your phone. You open your calendar the next morning and the meeting is there.

The weather widget on your desktop updates every hour. The clock synchronizes itself with atomic time servers. Your documents back up to a server farm you’ll never see. Your photos upload while you sleep.

Run netstat on your computer right now. Count the active connections. Dozens of processes you’ve never heard of are talking to servers you’ve never seen—fetching, syncing, checking, reporting. Your computer isn’t occasionally visiting the internet. It lives there. It’s a participant on the network, acting on your behalf, in the background, constantly.

The cyberspace that science fiction imagined—that neon elsewhere you’d jack into—never materialized. What happened was stranger. The network dissolved into everything. You stopped “going online” because there was no longer an offline to go from. The internet became plumbing: invisible, assumed, always on.

Once infrastructure is in place, the world reorganizes around it. Microsoft didn’t predict weather widgets or automatic updates or cloud sync. No one in 1995 sat down and designed the networked future. It got co-created. Once developers could assume networking existed, they built things that only made sense because that infrastructure was there. The applications emerged from the capabilities. Millions of developers suddenly had a capacity they could take for granted, and the explosion of what became possible was impossible to predict beforehand.

This Pattern Is Repeating

In June 2024, Microsoft shipped the Windows Copilot Runtime—a native AI layer built directly into the operating system. Not an app you install. Not a service you subscribe to. Plumbing. The OS now includes more than 40 machine learning models and a specialized small language model called Phi Silica, designed to run on your local hardware.

Apple made the same move. In October 2024, they rolled out Apple Intelligence—a 3 billion parameter model running natively on Apple silicon. The model lives in unified memory alongside everything else your computer does. It can see what’s on your screen. It can take action across apps. It can understand context in ways that a browser-based chatbot never could, because it’s not a visitor—it’s part of the house.

Both companies are building the same architecture: small, capable models embedded in the OS that can handle most tasks locally, routing to larger cloud models only when necessary. The operating system decides where computation happens—local chip, cloud server, hybrid—just like TCP/IP decides how packets get routed. Apps don’t need to think about it. They just call the API.

This unlocks something new: automatic behavior.

Right now, cloud-based AI features are almost always click-gated. You open ChatGPT. You ask a question. You wait for a response. Why? Because running inference in the cloud costs money. Why run expensive computation if the user might not use it?

But when the model runs locally on your device, the marginal cost per inference drops to nearly zero. Suddenly, your OS can do things without the user initiating.

Your computer could be constantly working on your behalf using AI, the way it constantly works on your behalf using networking.

And it can do this because your context is already there—your files, your data, everything your computer knows about you is local. There’s no round trip to a cloud service. No data leaving your machine. Just local intelligence working with local information.

Apps can assume AI exists the way they assume the file system exists, the way they assume networking exists.

And once apps can assume that, the effort to develop AI features disappears into the plumbing. Developers will build on whichever platform makes it easiest—whoever provides the simplest APIs, the fewest obstacles between an idea and a working feature.

Everyone Is Racing to Be the Plumbing

Whoever owns the plumbing layer becomes the gatekeeper. And gatekeeping is lucrative.

Apple’s App Store earned the company $27.4 billion in commissions in 2024—$10 billion from the U.S. alone.

If the next generation of applications are AI-enabled—and they will be—whoever controls the AI infrastructure controls which apps get built and where they’re distributed.

The economics are too large to ignore. This isn’t just about technical capability. It’s about defending and extending the most profitable layer of the stack.

Google sees this happening and has a problem. Chrome OS exists, but it runs on maybe 2% of the world’s computers—mostly in schools. They can’t own the operating system layer on the machines most people use for work.

But they don’t need to.

Chrome runs on 65% of all browsers worldwide. And increasingly, the browser is the platform that matters. Your documents live in Google Docs, your design work happens in Figma, your spreadsheets run in Airtable. The operating system launches Chrome, and then Chrome becomes the environment where actual work happens.

So Google is building AI into Chrome itself. In December 2024, they embedded Gemini Nano directly in the browser—a small language model that runs locally, processing data without it ever leaving your machine. Any web application can call it. The browser becomes the AI layer, sitting between web apps and AI capabilities the same way Windows and macOS sit between native apps and AI capabilities.

The platform doesn’t have to be the operating system. It just has to be where developers build and where users spend their time. For Microsoft and Apple, that’s the OS. For Google, it’s one layer up.

Building Infrastructure Is One Thing. Knowing How to Use It Is Another.

In November 2024, Windows president Pavan Davuluri announced that Windows would “evolve into an agentic OS.” The response was thousands of overwhelmingly negative replies. But what does an “agentic OS” actually look like?

Microsoft’s answer seemed to be: put a Copilot button everywhere—File Explorer, Notepad, Paint, Settings. Every application got AI integration whether it made sense or not. Users weren’t ready for it.

Then there’s Recall—a feature that would screenshot everything you do and make it searchable with AI. As an idea, it’s interesting. As an implementation, the privacy concerns were immediate and loud. Microsoft postponed it by a year. Now they’re backing off: removing Copilot buttons from apps, rethinking Recall, pausing new integrations.

But the Windows Copilot Runtime—the infrastructure—that’s staying.

This is typical early-infrastructure behavior. When you build new plumbing, you don’t immediately know the right way to surface it. That gets co-created over time, through experimentation and iteration. Not every attempt works. That’s normal.

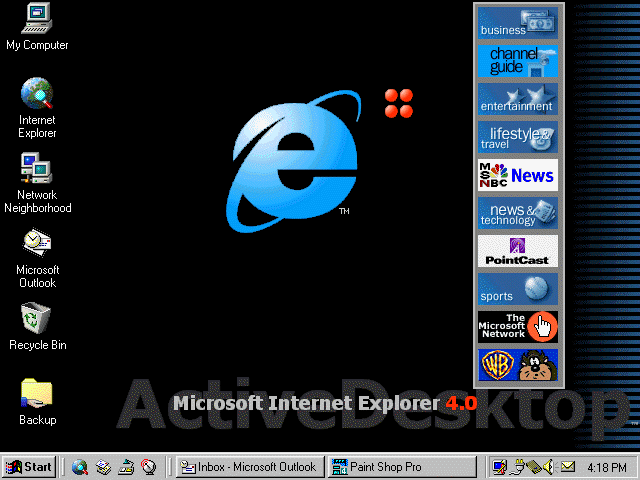

Windows 98 did the same thing. The networking infrastructure was there, and Microsoft’s answer to “what should an internet-aware desktop look like?” was Active Desktop. Your wallpaper could be a live web page. A toolbar of “Active Channels” delivered constantly updating content from Disney and Warner Bros. The desktop and the web were supposed to blur together.

Users hated it. Active Desktop was resource-heavy, unstable, and intrusive. Most people didn’t have fast enough connections to make it useful. By Windows Me, Microsoft had quietly downplayed the feature.

But here’s what didn’t go away: the networking stack. TCP/IP stayed. Background updates stayed. Automatic syncing stayed. The plumbing remained; only the gaudy UX got stripped out.

That’s what’s happening now. Microsoft is pulling back Copilot buttons and reconsidering Recall, but the Windows Copilot Runtime—those 40+ models running in the background, the APIs that let any app access AI—that’s staying. The infrastructure is going in regardless of whether users like the first attempt at exposing it.

Because once the plumbing exists, you can iterate on the UX. You can try different approaches, see what users actually want, refine the experience. Active Desktop failed, but years later we got live tiles, widgets, and web-connected features that people actually used. The infrastructure made experimentation possible.

When Infrastructure Becomes Invisible

Here’s the thing about plumbing: once it’s built in, you can’t imagine the world without it.

We know the value of networking not because we think about it, but because we’ve stopped thinking about it. You only notice the internet when it’s gone—when you’re on a plane and that little Wi-Fi icon shows no connection. The infrastructure’s absence reveals what you were taking for granted.

That’s what’s coming with AI. Not a browser tab you open. Not a destination you visit. Just something your computer is, the way it’s always online.

We’re watching AI stop being something you do and start being something your computer is.