The Promise to Pay the Agent

How a 14th-century merchant’s solution to moving money foreshadows AI commerce—and its risks

In 1397, a merchant in Prato needed English wool.

Francesco Datini had built a successful business trading silk, weapons, and cloth across Europe. But the finest wool came from England, and Prato sat 1,500 kilometers away, across the Alps and through territories controlled by competing city-states. The wool merchants in London wouldn’t ship without payment. And carrying enough gold florins to buy wholesale quantities meant crossing bandit-infested roads where armed men waited for exactly that kind of cargo.

Datini solved this problem by not sending gold at all. He sent a man with a piece of paper.

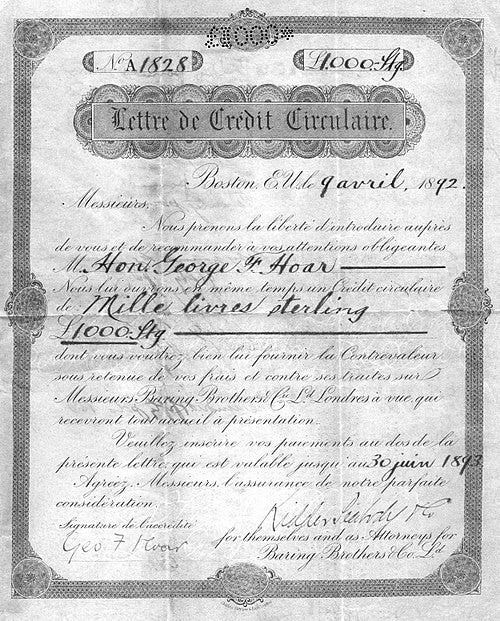

The paper was a letter of credit from the Medici bank, sealed and cryptographically signed (by the standards of the day—wax seals and handwritten signatures that bankers could verify). It said, in effect: “I promise to pay the bearer of this letter up to 500 florins.” His factor—a trusted agent—would travel for weeks to reach London, carrying nothing more valuable than that sealed document. When he arrived, he’d present it to a correspondent bank, which would verify the seal and signature. If everything checked out, the factor would receive English pounds, use them to negotiate the best wool prices he could find, arrange for shipping back to Prato, and send word to Datini about the transaction.

We know about Datini’s business in unusual detail because in 1870, workers renovating his palazzo in Prato discovered a hidden stairwell containing 150,000 letters and 500 account books. The archive reveals a merchant who operated simultaneously in Florence, Pisa, Genoa, Avignon, Barcelona, and Valencia—buying, selling, and managing complex financial arrangements across distances that would take months to traverse. His letters discuss the constant dangers: bandits, pirates, wars between city-states, and the simple risk of roads where a bag of gold made you a target.

Letters of credit changed the economics of commerce. Without them, trade was limited by how much gold one person could safely carry, how far they could travel, and how many places they could personally visit. With them, a merchant could send multiple agents to multiple cities simultaneously. The agent in London buying wool didn’t need to wait for the agent in Barcelona selling silk to return with payment. Commerce could expand beyond what any individual could accomplish by being physically present.

The key innovation wasn’t the paper itself. It was solving the delegation problem: how do you prove that someone has authority to spend your money when you’re not there to click “approve”?

Three centuries later, money became information. Paper currency replaced gold. Then digital transfers replaced paper. We got comfortable with the idea that money is just verified information moving through trusted networks.

Now we’re making another transition. Information is becoming decisions.

AI agents can search the web, write code, analyze data, and coordinate complex tasks. They operate continuously, monitoring thousands of signals, responding to opportunities faster than humans can. The obvious next step is letting them complete transactions. “Buy concert tickets the moment they go on sale.” “Order more paper towels when we run low.” “Book the cheapest flight to Boston next Tuesday.”

But here’s the problem: our payment systems still assume a human is clicking “buy.” And just handing your credit card to an AI agent—like giving a blank check to someone you barely know—raises questions that make medieval banditry look straightforward.

What happens when your agent misinterprets “buy me a nice dress for the wedding” and optimizes for “options” by purchasing forty dresses? Who’s liable when it books a $5,000 hotel room because “best available” didn’t specify a price limit? How do merchants verify that an agent’s request actually reflects your intent? How do credit card companies assess fraud risk when the human isn’t present?

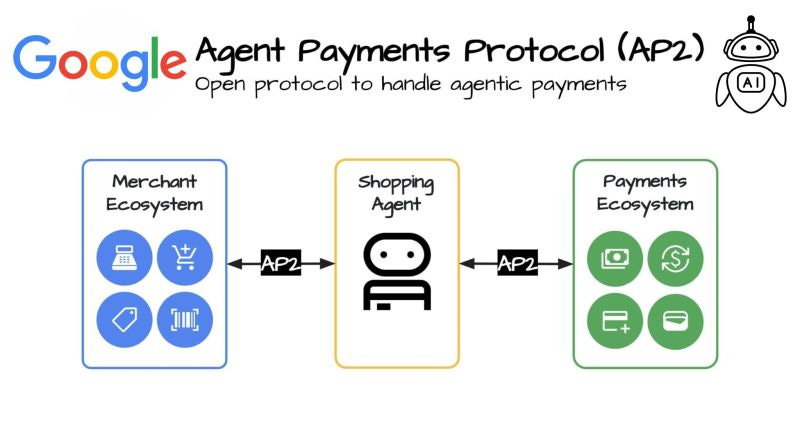

In September 2025, Google announced a protocol to solve these problems. The Agent Payments Protocol (AP2) is being developed with more than 60 companies—payment processors like Mastercard and PayPal, merchants like Etsy and Shopee, technology companies like Salesforce and Coinbase. It’s an attempt to build the trust infrastructure for a new kind of commerce.

Datini needed sealed letters to prove his factor had authority to spend florins in London. We need cryptographically signed mandates to prove our agents have authority to spend dollars on Amazon. The technology is different. The problem is the same.

The Friction Problem

Why even hand authority to an agent? It seems reckless.

But consider the transactions that don’t happen today. Your dermatologist has a cancellation list, but checking it means calling during business hours when you’re not available. By the time you find out there’s an opening, someone else took it. Coordination costs killed the transaction.

Or a restaurant owner’s flour supplier is out of stock. Finding a replacement could take hours—calling suppliers, comparing prices, verifying quality. But lunch orders are starting. The coordination cost exceeds his tolerance.

These aren’t new problems. Datini faced the same constraint. He couldn’t move gold fast enough to catch market opportunities in London while managing business in Florence. He couldn’t be in multiple cities simultaneously to negotiate deals when prices shifted. The opportunities existed. The money existed. But coordination costs killed transactions.

Today, we can’t monitor enough places simultaneously. We can’t act fast enough on timing-dependent opportunities. Same problem, different century.

The economic cost is real. Customers don’t get what they want—they’re willing to pay, but can’t coordinate. Merchants don’t sell inventory they have—it’s sitting there, customers exist, but friction kills the transaction. Both parties lose to coordination costs.

How AP2 Addresses This

Our payment infrastructure still assumes a human clicks “buy.” Card present versus card not present—both designed for human authorization. Agents introduce a third actor. They need to prove authorization without a human present for each transaction.

AP2 solves this with two delegation modes, matching how you’d work with a human assistant.

When you’re actively working together, you give broad direction and approve specifics. “Find running shoes under $150.” The agent searches, presents options, you pick one. Each step creates a cryptographic record: your original request, the options found, your approval. By the time payment executes, there’s a complete chain proving the agent followed your instructions.

When you’re not available, you authorize upfront with clear constraints. “Buy concert tickets when they drop, maximum $200 each.” The agent monitors, and when conditions are met, executes automatically. You wake up to tickets and a complete audit trail showing exactly how your instructions were followed.

The key is the audit trail. You can verify the agent followed your intent. Merchants can verify the agent had authority. Payment processors can assess risk based on the cryptographic chain.

AP2 works with any payment method—credit cards, bank transfers, stablecoins. It’s just the authorization layer.

What Changes

When agents can transact securely, markets that don’t exist today become possible.

Consider the dermatologist appointment. Your agent monitors cancellation lists, cross-checks your calendar and insurance, and books automatically. The coordination that would take hours of phone tag happens in seconds.

Or the restaurant supply chain. The owner’s agent detects the flour shortage, queries alternative suppliers, verifies quality, and executes the purchase. No phone calls. No stepping away from prep. The transaction happens because monitoring costs dropped to zero.

This extends beyond consumer commerce. Companies are exploring autonomous procurement, automatic software scaling based on usage, supply chain automation where purchase orders flow between systems without human approval for routine transactions.

In pre-industrial markets, everything was personalized negotiation. Mass production forced standardization because coordinating custom deals didn’t scale. Agent-based commerce returns to personalization but makes it scale. Not just automating current commerce, but enabling market structures we abandoned for efficiency reasons.

Datini could operate across six cities because letters of credit let him delegate purchasing authority safely. AP2 lets agents operate across the entire digital marketplace—monitoring, negotiating, assembling deals—while you sleep.

What We Risk

But AP2 solves the authorization problem, not the trust problem. And trust isn’t the only problem.

Datini didn’t just trust letters of credit—he trusted his factors. His 150,000 letters reveal constant correspondence: checking prices, questioning decisions, building understanding over years. His factors weren’t just authorized. They were recruited from family or long-term employees, trained, tested on small transactions before large ones. Trust built through repeated interactions.

We face the same challenge. There’s a spectrum from “buy these specific concert tickets at this exact price” to “buy good clothes for tomorrow’s meeting.” The first requires verification. The second requires understanding. Today’s agents handle concrete mandates well. But judgment calls—the “understand what I want better than I specified it”—require the kind of relationship Datini built with his factors over years.

But speed introduces problems trust can’t solve. We already see the pattern with Ticketmaster scalper bots—illegal, but effective. When 10,000 “legitimate” personal agents all bid for concert tickets simultaneously, each following its owner’s $500 mandate, it’s not fraud. It’s speed arbitrage. Those with faster, more sophisticated agents win.

Hedge funds already deploy trading bots that exploit millisecond price gaps across markets. Agent commerce extends this logic to every transaction. The benefit flows to whoever can afford the best algorithms. Automation doesn’t level the field—it tilts it toward those who can optimize fastest.

And when agents automate everything—booking flights, negotiating bills, reordering groceries, buying gifts—what happens to deliberation itself? The friction we’re eliminating also forced choice. Convenience replaces discernment. If your agent knows your preferences better than you do, what does “taste” or “patience” even mean?

Datini didn’t hand his factors letters of credit immediately. He worked with them for years first. AP2 provides the infrastructure—the cryptographic proof that an agent has permission to spend your money. But infrastructure enables both opportunity and problems.

The infrastructure comes first. But learning to trust it, use it wisely, and understand what we lose in the bargain—that comes slowly.