The Echo of Demand

What a 1960s supply chain simulation can tell us about the AI infrastructure boom

Week 8. You own a small brewery—a regional Mexican lager that’s found its niche in local restaurants and corner stores. The order sheet says zero cases. Your warehouse is stacked with beer nobody’s buying.

A month ago, everything was steady. Four cases a week from your distributor, same as it had been for as long as you could remember. Then the order came in: twenty cases. Five times the normal run rate, overnight.

You shipped what you had and faced a sixteen-case backlog. A signal that strong meant something downstream had clicked. The expensive campaign you had bet on, the new distributor, whatever it was. You added a second shift, authorized overtime, expedited raw materials. You weren’t going to miss the moment.

Then the orders fell. Twelve. Eight. This week: zero.

The facilitator calls the game.

The Game That Never Changes

You’ve been playing the Beer Game, a supply chain simulation MIT has run for more than fifty years. The players change—Harvard MBAs, Fortune 500 executives, engineering students—but the outcome never does. Rational people, reasonable decisions, real information: same disaster every time.

Jay Forrester built the game in the 1960s after watching GE’s appliance factories swing between three shifts and mass layoffs with no obvious external cause. Management blamed market forces—unpredictable customer demand, competitive pressure. Forrester ran a simulation and proved otherwise: the oscillations came from inside the system, from the structure of how decisions and delays compounded each other. The problem isn’t the players. It’s the very structure.

This game has been demonstrating real-world patterns for decades. And, it might be a good lens for understanding the AI infrastructure build-out.

But first, let’s see how we got here.

Four Weeks to Five-Fold

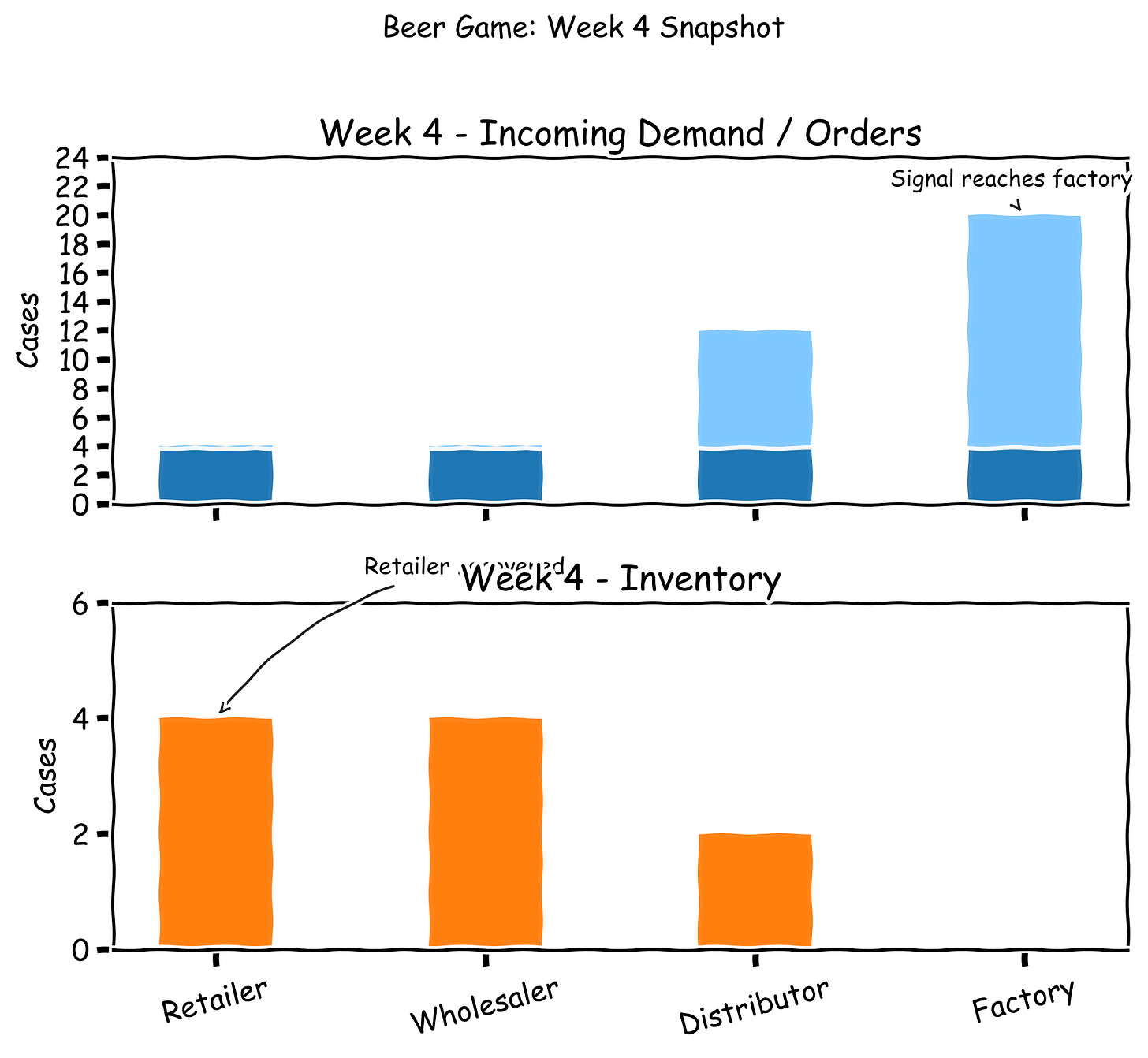

To make the mechanics clear, we’re going to simplify: one retailer, one wholesaler, one distributor, one factory. A single product moving through a single supply chain.

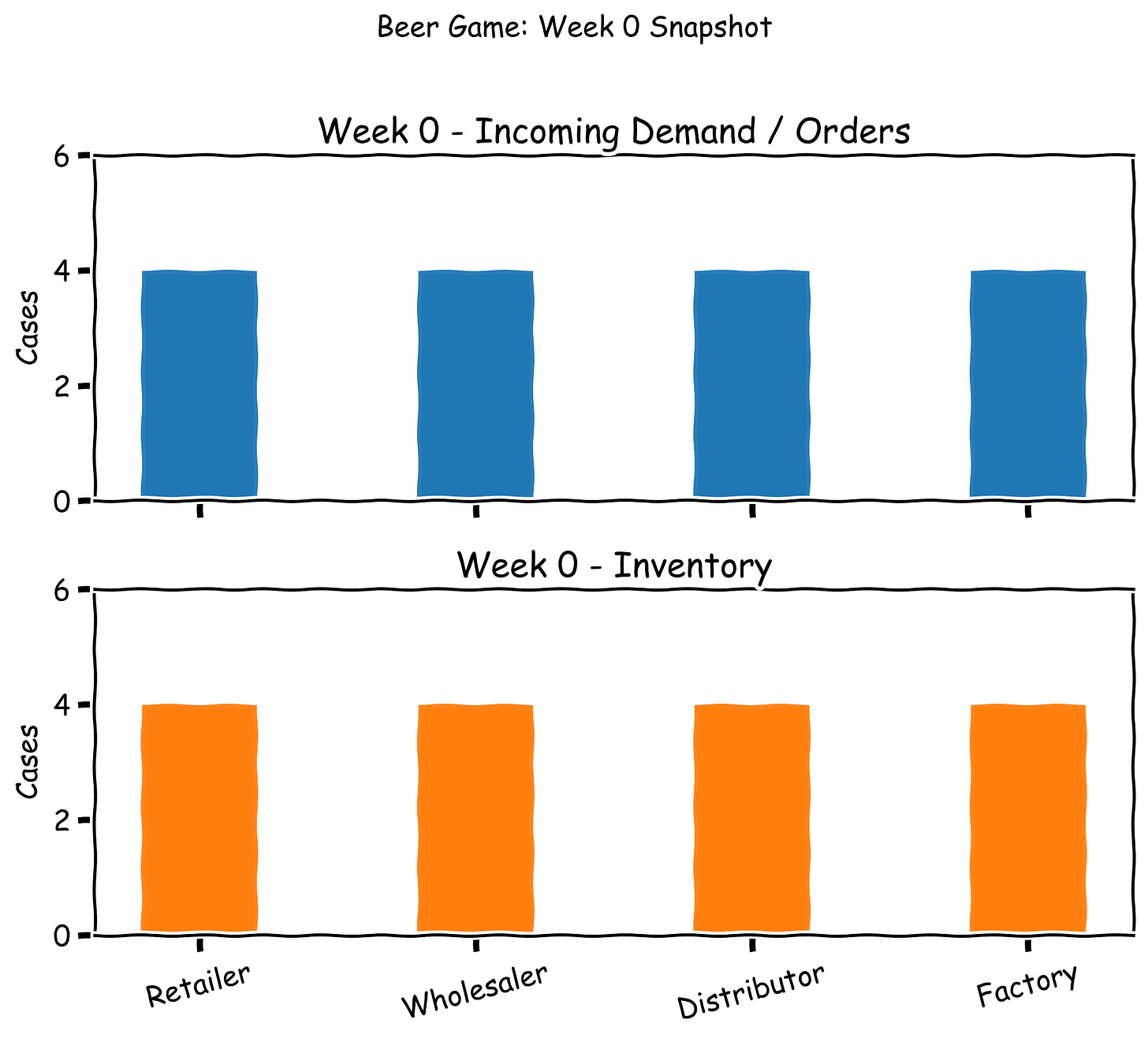

The game starts in equilibrium. Customers buy four cases of beer a week, and that number flows unchanged through every layer—retailer to wholesaler to distributor to factory. Everyone orders four, ships four, keeps four cases as a buffer. Just enough to absorb a small demand shift without panic, not enough to tie up capital. The supply chain hums along.

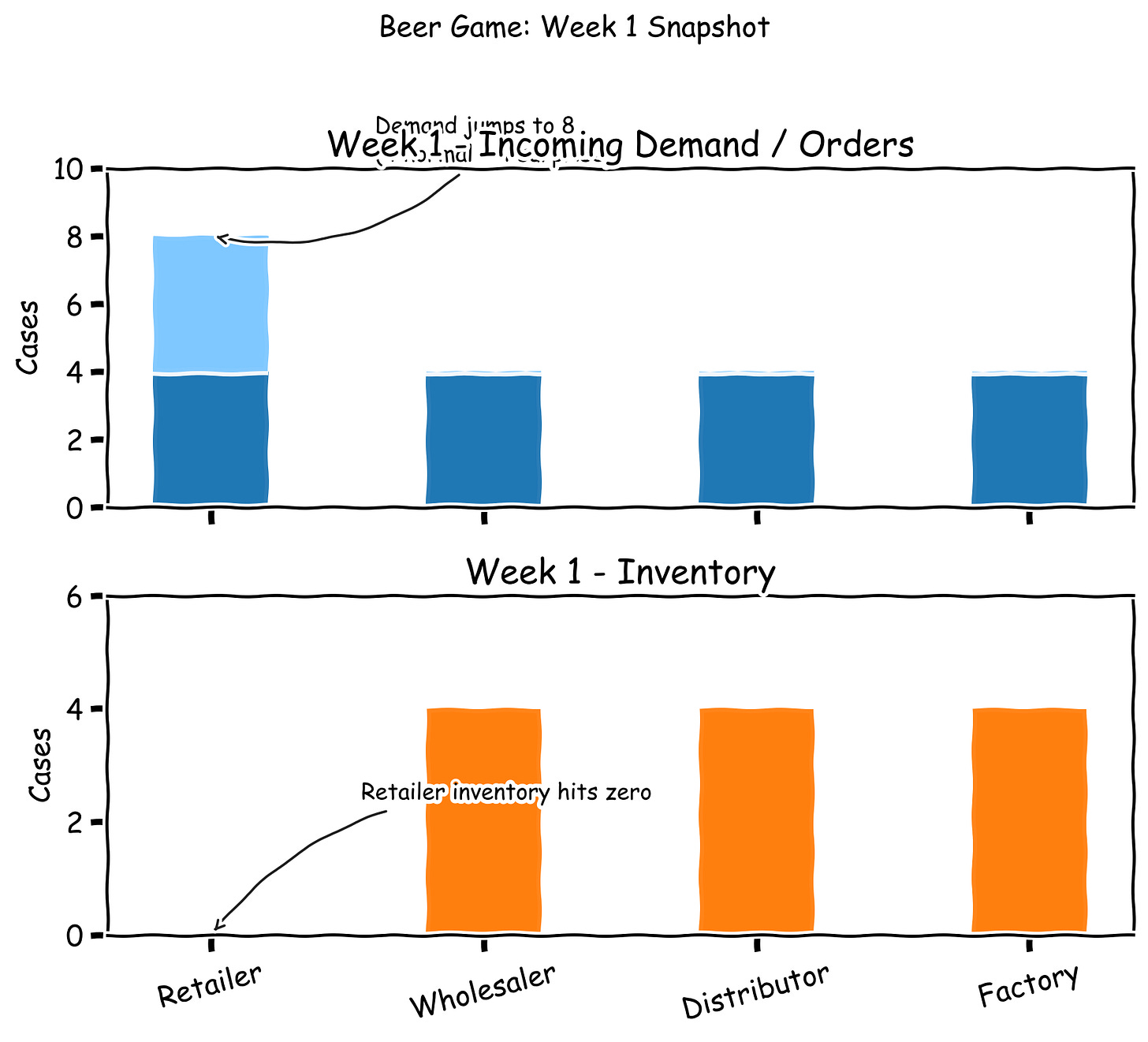

Then one week, something shifts. Maybe a local promotion. Maybe a random fad for Mexican beer. Whatever the reason, customers order eight cases instead of four.

The retailer’s shelf is empty by Friday. The four-case buffer vanished in a single day. Empty shelves mean lost sales, and so the retailer orders twelve-cases—eight to cover what looks like sustained demand, four to rebuild the vanished buffer.

But there’s a three-week lag between ordering and delivery. By the time Week 2 rolls around, demand has already dropped back to four. The retailer sees this, pulls the next order down to eight as a cautious correction, and feels good about adapting to what was probably just a temporary spike.

That original twelve-case order, though? Already on its way upstream.

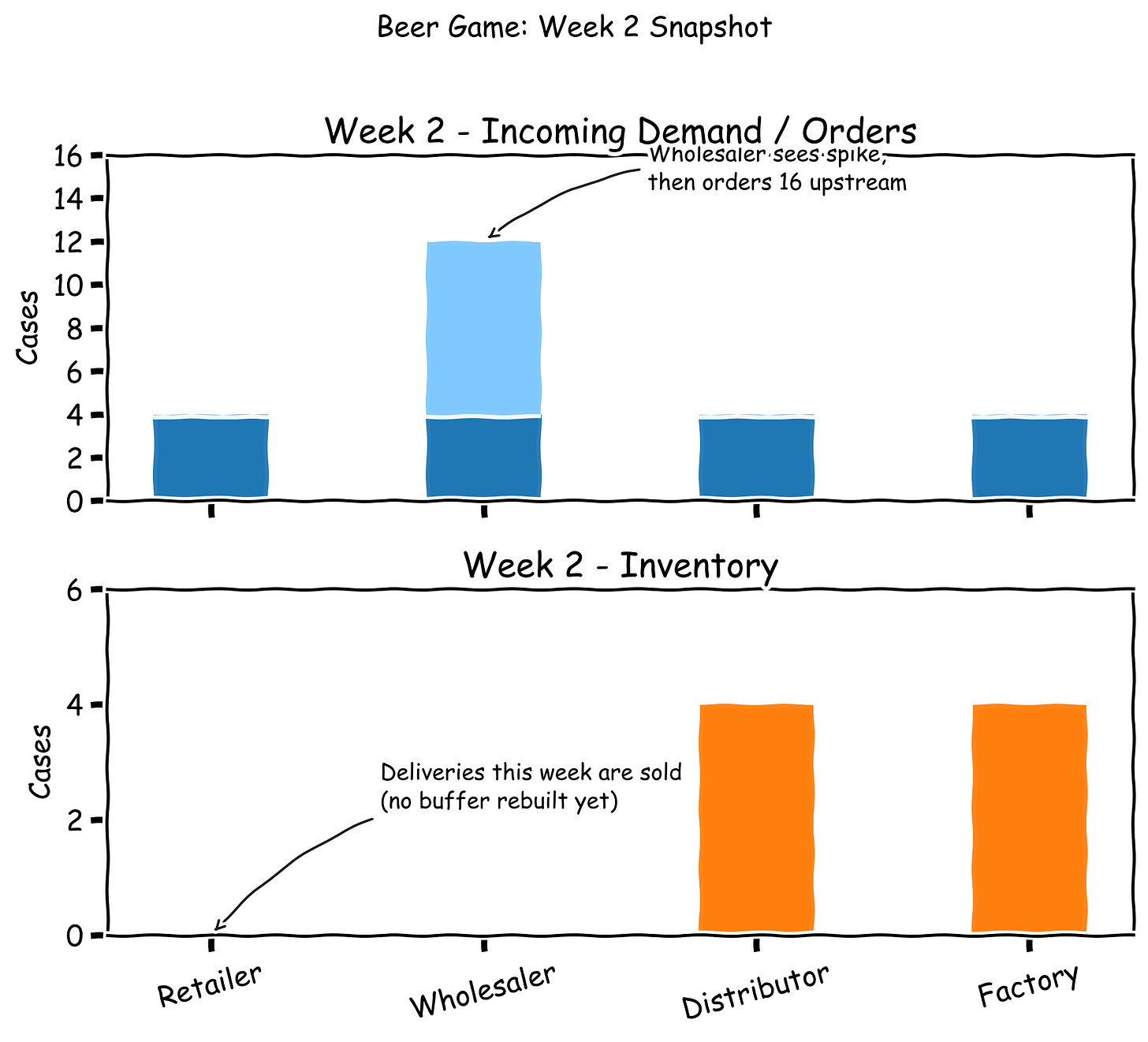

The wholesaler sees twelve cases on the order form—triple the normal run rate. Business must be picking up. They ship the four cases in inventory and face an eight-case shortfall. The warehouse is empty, and the choice is obvious: order sixteen from the distributor. Twelve to meet the new demand level, four to rebuild the buffer.

The retailer’s new order—the eight cases that says “it was just a spike, we’re back to normal”—won’t reach the wholesaler until next week. By then, the sixteen-case order has already hit the distributor.

The distributor sees sixteen cases—four times normal. Same pattern: ship the four in stock, stare at the twelve-case gap, order twenty upstream to cover the surge and rebuild the safety margin. The wave is building.

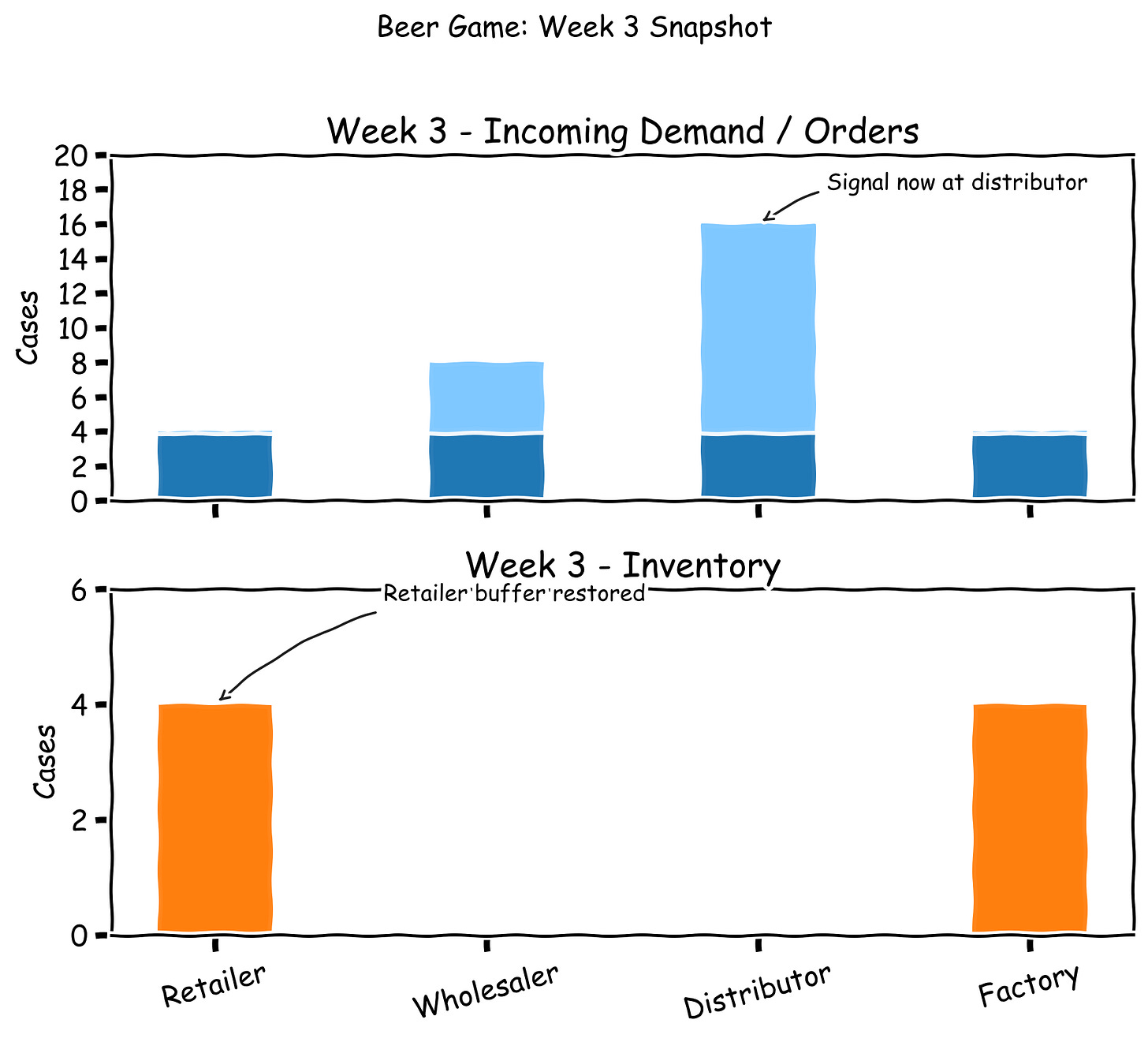

The order arrives at your factory: twenty cases. Five times the normal run. You ship the four you have ready, clear out finished goods, and look at the sixteen-case backlog. This isn’t a blip—this is the trajectory you’ve been waiting for. Time to scale. Second shift, overtime, expedited materials. The breakthrough moment.

What you can’t see from the factory floor: the correction was already in motion three weeks ago. The retailer had dialed back to eight cases by Week 2. But each layer upstream was still reacting to the signal from the week before—adding buffer, staying one step behind the truth. By the time the wave reached you, the original spike had been gone for three weeks.

You weren’t responding to demand. You were responding to the echo of demand.

Echo or Signal?

Every decision was rational. The customer demand spike was real—people genuinely wanted Mexican beer that week. Each player saw empty inventory, ordered more to cover the shortfall and rebuild their buffer. Nobody fabricated numbers. Nobody panicked.

But a one-week spike that settled immediately amplified into a five-fold surge by the time it reached the factory. This is the bullwhip effect—small fluctuations at retail become large swings upstream. The structure is almost elegant in its simplicity: time delays mean each layer can only see the order from directly below, not the original customer demand. Inventory runs out, you order more. Your partner’s order spikes, you add buffer.

Now add back the complexity we stripped out. Multiple retailers, each responding independently. Multi-week demand patterns that look like trends. Competing signals from different channels. And crucially: narrative.

By the time that twenty-case order reaches your factory, it doesn’t land as “echo of a temporary spike.” It lands as confirmation. The marketing campaign worked. The regional expansion paid off. Time to go national. Champagne breaks out. The executive team celebrates. The board approves new facilities, new hires, new capacity.

The structure creates the outcome. But the narrative shapes what happens next.

Cisco’s $2.25 Billion Echo

This simulation is a pattern that plays out with real consequences repeatedly.

Cisco experienced this in 2001. The dot-com boom was real—startups launching daily, venture capital flowing freely, businesses racing to get online. Every one of those startups needed routers. Every ISP was expanding capacity. Every telecom was building out infrastructure. The demand was genuine.

Cisco’s contract manufacturers were ordering independently—each responding to their own slice of the orders, each adding buffer.

By the time those orders reached Cisco’s supply chain, they validated the narrative - the internet was taking over, Cisco was winning. Hiring surged, production expanded, new facilities broke ground. The stock soared.

Then the boom ended. Cisco held over $2.25 billion in unsold inventory, the stock fell 84%, and eight thousand jobs disappeared.

Same game. Different product.

Same Game, Longer Delays

Now let’s look at AI infrastructure through the lens of the beer game. We don’t have the full story—companies don’t publish their internal decision-making, and supply chains are complex. But we can trace the basic structure: customers use AI models, AI labs like Anthropic power those models by renting compute from cloud providers (hyperscalers) like AWS, those providers order datacenters from builders, and builders need power from utilities. We could trace a similar supply chain to semiconductor and other suppliers as well but we’ll stick with data center construction and power since that’s in the news lately.

Like in our beer story, we start with a demand spike. When Claude 3 launched in March 2024, coding assistants could finally work longer on more complicated tasks. Claude Code hit a $1 billion run rate as developers and non-developers alike rushed to try it. Anthropic’s total revenue climbed from $1 billion at the end of 2024 to a $9 billion annualized run rate by the end of 2025, with enterprise customers driving 80% of that revenue. The demand was real. But is this the moment AI coding permanently changes how software gets built—or is everyone just trying Mexican beer because it’s Cinco de Mayo?

And just like the retailer who ordered twelve cases instead of four, Anthropic needed to add buffer. Running out of compute means users leave for competitors. Through September 2025, the company spent $2.66 billion on AWS compute against $2.55 billion in revenue—and inference costs came in 23% higher than the company expected, compressing margins and pushing expenses above plan. The orders flowing to AWS were already larger than Anthropic had budgeted for.

Pulling back wasn’t an option. OpenAI exited 2025 at roughly $20 billion in annualized revenue with 900 million weekly active users. Anthropic, almost entirely dependent on enterprise contracts, was burning cash at a similar rate with a fraction of the user base. Slowing down meant losing customers to a competitor with a hundred times the audience. So Anthropic is planning for $18 billion in revenue this year, $55 billion next year, with break-even pushed to 2028. Training costs alone: $12 billion this year, $23 billion next. The order flowing upstream to AWS keeps getting bigger.

Anthropic’s primary cloud provider is AWS. Like the wholesaler receiving that twelve-case order, AWS sees the signal and responds. But they’re not just seeing Anthropic. They’re seeing orders from other AI labs too, each booking capacity independently. AWS can’t afford to run out and lose customers to Microsoft or Google. Back in January 2023, they’d announced a $35 billion Virginia commitment by 2040, and by October of that year were filing applications for $11 billion in datacenters in rural Louisa County. The expansion continued: in October 2025, they activated a massive computing site in Indiana. Build bigger, add buffer, don’t run out.

Builders watching this expansion saw the orders multiply. Turner Construction’s datacenter revenue nearly doubled—from $3.6 billion in 2024 to $6.4 billion in just nine months of 2025. Orders were coming from AWS, Microsoft, Google—each hyperscaler ordering independently. Same pattern as the factory seeing the twenty-case order: scale up fast, hire more crews.

Dominion Energy, Virginia’s largest utility, watched the Northern Virginia corridor transform. Datacenter projects were appearing in every forecast, and the company’s contracted capacity jumped from 21 gigawatts in July 2024 to 40 gigawatts a year later—an 88% increase. Dominion’s response: a five-year capital plan totaling $50.1 billion, with $41 billion earmarked for Virginia’s grid, generation, and transmission projects to support datacenters. New generation capacity, transmission upgrades, substations.

But the Beer Game’s real lesson is about timing. In the simulation, the wave comes and goes in weeks—fast enough to see the full cycle, fast enough for everyone to see. In AI infrastructure, the cycle runs on years. Power infrastructure takes three to five years to build. Commitments made in 2023 won’t complete until 2028. If the demand wave breaks before construction finishes, you don’t just end up with excess inventory. You end up with half-built infrastructure.

We’ve seen this pattern before. China’s real estate boom was amazing until it wasn’t. Now China has entire cities of unfinished apartment blocks, half-built infrastructure projects, and stranded capital. The wave broke before construction finished.

Same game. Different product.

Knowing Doesn’t Help

The Beer Game is one of the most-taught supply chain lesson in business history. You’ve probably played it yourself. You know about the bullwhip. You can see the structure. That was never the problem.

The problem is that you didn’t start a brewery to study supply chains. You started it because you believe Mexican beer’s moment is coming—that it stops being the niche choice and becomes the default. Four cases a week keeps the lights on. It was never the plan. The plan was always the hockey stick: the quarter where orders jump and keep jumping, where the revenue curve bends and doesn’t bend back. You’ve been waiting for it since you signed the lease.

The bullwhip looks exactly like the hockey stick. Same spike on the order sheet. Same revenue curve. Same boardroom energy. And when it arrives, everything around you confirms it. The stock price climbs. Your employees’ options, worth nothing at four cases a week, suddenly mean something. The board stops asking “when” and starts asking “how fast.” Analysts upgrade. Investors come calling. Every signal you’re receiving says the moment has arrived.

What would it take to look at all of that and say: it’s just Cinco de Mayo?