The AI Agent Career Ladder

How we'll learn to promote artificial intelligence

In October 2014, several hundred people gathered at Hawthorne Airport expecting a car announcement. Tesla CEO Elon Musk—much more liked back then—had been teasing something called "the D" for weeks. The automotive press had done their homework: dual-motor, all-wheel-drive Model S. Better traction, faster acceleration.

They got that. The P85D would accelerate from 0 to 60 mph in 3.2 seconds, matching the McLaren F1. "This car is nuts," Musk told the crowd. "It's like taking off from a carrier deck."

Then he dropped the bombshell. "There's something else." The screen behind him lit up with a single word: "Autopilot."

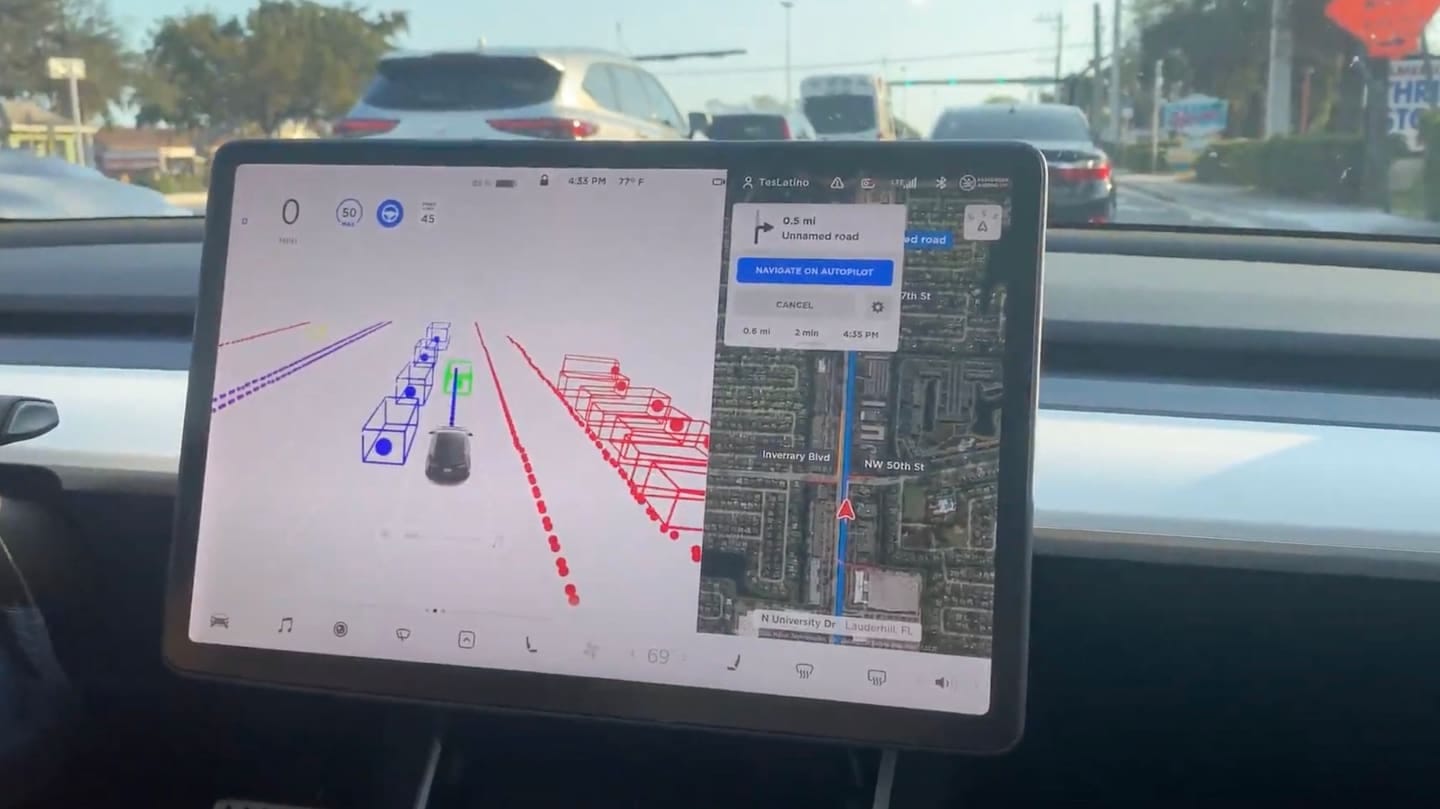

The car could park itself, sense obstacles, adjust its speed automatically. Musk cautioned that it wasn't "fully autonomous driving"—you couldn't fall asleep at the wheel—but he'd just given driver assistance technology a name that would stick.

The chaos began within months.

Mercedes-Benz announced "Drive Pilot." Audi countered with "Traffic Jam Pilot." BMW rolled out "Driving Assistant" features. GM launched "Super Cruise." Ford followed with "BlueCruise." Every automaker suddenly needed their own catchy name for similar driver assistance technologies.

Nobody knew what any of these names actually meant.

Was Tesla's "Autopilot" the same as Mercedes' "Drive Pilot"? Could Audi's system do everything BMW's could? When Tesla promised "Full Self-Driving," were they talking about the same thing as GM's "Super Cruise"?

Marketing departments ran wild with futuristic names while consumers, regulators, and engineers tried to decode what each system could actually do. Tesla kept promising full autonomy "next year"—a promise repeated annually for the next decade. Other companies made their own bold claims, each trying to sound more advanced than the competition.

By 2016, the confusion had reached a breaking point. Consumers didn't know what they were buying. Regulators didn't know what they were regulating.

Fortunately, someone had already been working on that problem.

The Standards Solution

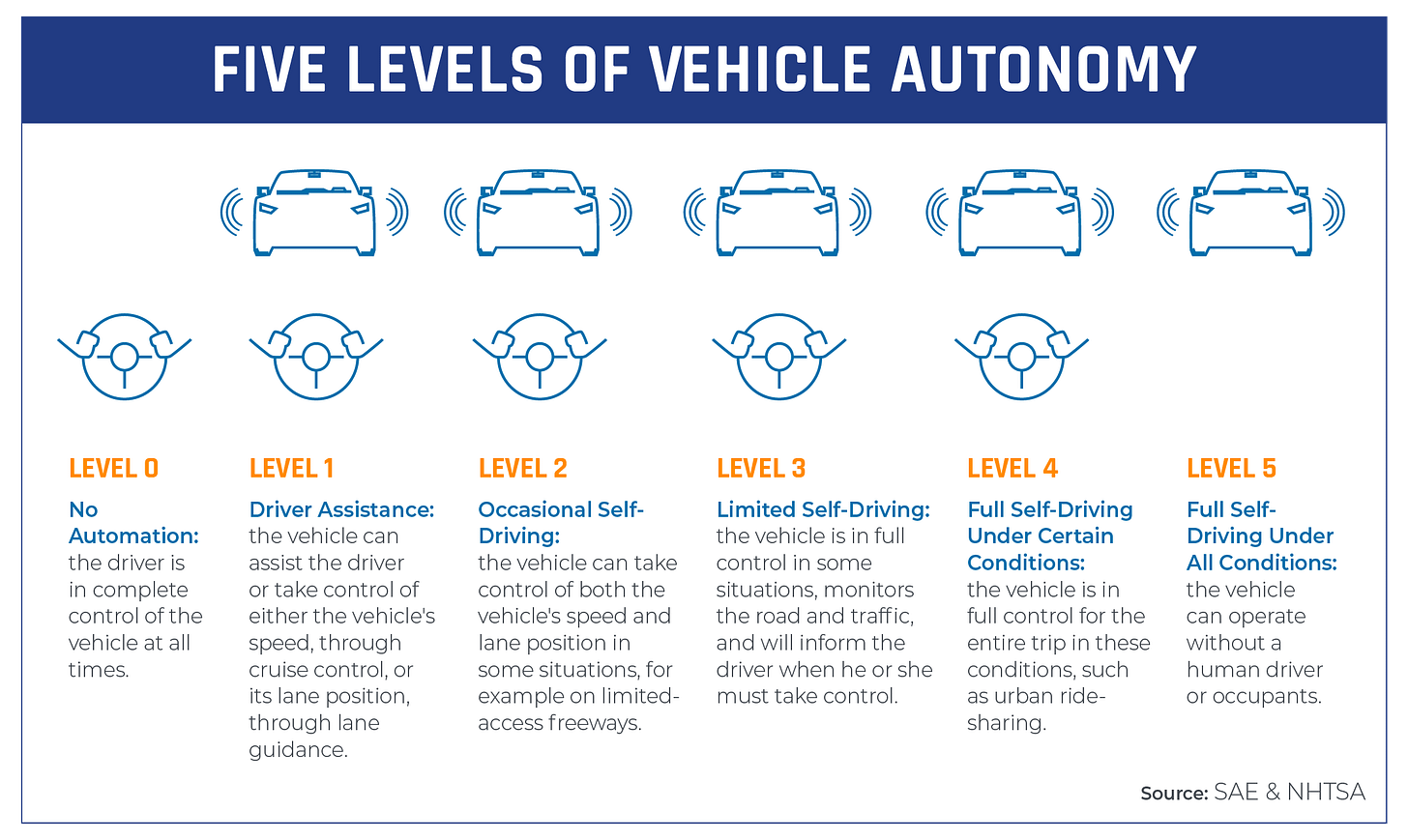

The Society of Automotive Engineers had published SAE J3016 in January 2014—the same year Musk made his Autopilot announcement. The standard defined six levels of driving automation, from Level 0 (no automation) to Level 5 (full automation). It wasn't flashy. It didn't have a catchy marketing name. But it provided something the industry desperately needed: a common language.

Level 0 meant the human did everything. Level 1 meant the car could help with either steering or speed, but not both. Level 2 meant it could handle both, but the human had to stay alert. Level 3 meant the car could drive itself in specific conditions, but the human had to be ready to take over. Level 4 meant full automation within defined areas. Level 5 meant the car could drive anywhere a human could.

The standard was updated in 2016 and 2021 as understanding evolved, but the basic framework stuck. Tesla's "Autopilot" was Level 2. Mercedes' "Drive Pilot" was Level 3. GM's "Super Cruise" was also Level 2, despite the different name.

By 2018, most industry discussions used SAE levels as reference points. Consumers could finally compare systems. Regulators could write appropriate policies. Engineers could focus on building technology instead of explaining marketing terms.

The chaos had been tamed by a simple framework: six levels that described what the system could actually do, not what it sounded like it could do.

Ten Years Later, Same Script

Ten years later, we're watching the same movie again. This time it's not Elon Musk at Hawthorne Airport—it's Sam Altman at OpenAI's DevDay in San Francisco, telling developers that "2025 is when agents will work." It's Satya Nadella at Microsoft Build, promising that "we are bringing real joy and a sense of wonder back to creation" with AI agents that understand us instead of the other way around. It's a parade of startup founders—70 out of 144 companies in Y Combinator's spring 2025 batch alone—each promising their AI agent will be the one to finally automate everything.

The promises sound familiar. Altman talks about agents that will "materially change the output of companies." Nadella envisions "computers that understand us, instead of us having to understand computers." Startup pitch decks overflow with claims about agents that will handle your email, manage your calendar, and revolutionize your workflow.

The chaos is here.

Every company uses different terms for what are often similar capabilities. Marketing departments are running wild with futuristic names while consumers, businesses, and even developers try to decode what each "agent" can actually do.

Sound familiar?

The AI industry is having its 2014 automotive moment. We have the same problems: no standardized terminology, marketing claims that outpace reality, and confusion about what different systems can actually accomplish.

But this time, the industry is learning from automotive's playbook.

The Emerging Framework

Multiple companies are developing frameworks that explicitly mirror the automotive approach. Sema4.ai has a five-level system. Vellum AI created six levels that directly reference the automotive standard. NVIDIA, Cisco, and AWS have their own versions.

The emerging consensus looks like this:

Level 0: Basic automation—scripts and macros that follow predetermined rules.

Level 1: AI-assisted—systems powered by large language models but controlled by humans.

Level 2: Partial autonomy—AI that can control specific parts of a workflow without human intervention.

Level 3: Agent-driven workflow—AI that can take a high-level goal and execute a sequence of actions to achieve it.

Level 4: Collaborative agents—multiple AI systems working together on complex tasks.

Level 5: Fully autonomous—AI that can operate independently across any domain (what we might call AGI).

The parallels to automotive levels aren't accidental. The tech industry watched how SAE J3016 brought order to automotive chaos and decided to copy the homework.

The Familiar Pattern

But here's where it gets interesting. This progression—from following scripts to setting strategic direction—isn't just familiar from cars and AI. It's exactly how we integrate new people into organizations.

Consider how Google handles new software engineers. When you join as an L3 (entry-level developer), you don't get the keys to Gmail's servers on day one. You handle individual tasks under two weeks with guidance. You need code reviews. You follow explicit instructions.

Prove you can handle that reliably, and you get promoted to L4—now you can work on medium-to-large features independently, but you're still not setting the agenda. Prove yourself there, and you reach L5, where you finally get to lead projects, make design decisions, and guide junior engineers.

Amazon follows the same pattern: SDE I needs guidance, SDE II gets "more significant responsibilities," and by Principal SDE, you "deliver with complete independence and lead component level direction."

This isn't unique to tech. It's how we learn to trust and delegate nearly everywhere humans organize capability.

The military brings in privates who follow orders, prove themselves reliable, and gradually earn the right to make decisions—from corporals leading small teams to generals setting strategic direction. Medical training follows the same arc: medical students observe, residents practice under supervision, attending physicians work independently, and department heads shape entire programs.

Each level requires proving competence at the previous level. You don't promote someone to senior engineer just because they're smart—you promote them because they've demonstrated they can handle junior-level responsibilities reliably, consistently, and independently.

The Real Work Begins

This pattern reveals that AI autonomy levels emerging today aren't just about organizing technical capabilities. They're about preparing to integrate artificial intelligence into human organizations using the same trust-building frameworks we've always used.

So here's what's likely to happen. Brand names aside—whether it's called "Operator," "Copilot," or "Agent"—every organization is quietly asking the same question: What level of autonomy are we comfortable giving this AI system?

But unlike cars, there won't be universal standards. The automotive industry could standardize because driving is driving. But work is organizational, and organizations have wildly different risk tolerances, cultures, and requirements.

This is exactly what companies do when they grow. At some point, they stop and ask: What does it mean to hire a Level 1 engineer? A Level 1 engineer at a startup might have more autonomy than a Level 3 at Google—and we're going to have to figure out what that means for AI agents too.

Each organization will have to build its own AI agent career ladder. Define what Level 1 agent responsibilities look like. Can a L1 support agent issue refunds? Upto what amount?

This isn't about installing a software app and being done with it. This is about re-engineering the corporation to include artificial intelligence. The hard work isn't just building the AI—it's building the career ladder. Learning to evaluate performance, set boundaries, and systematically increase the responsibilities we delegate to these new members of our organizations.

The future of AI isn't just about the technology getting smarter. It's about organizations getting better at learning to trust.

![Google Software Engineer Levels: Roles and Expectations [With Salary] - DEV Community Google Software Engineer Levels: Roles and Expectations [With Salary] - DEV Community](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!r2up!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4c4d224a-2ab6-48a2-b9fc-f372ee392f2b_800x662.webp)