The AI Adoption Paradox: How Gatekeepers Resist the Better, Faster, Cheaper Future

Exploring how professional organizations and unions shape the adoption of AI, even when it promises to make things better, faster, and cheaper.

The rapid rise of generative AI has sparked a lively debate about its potential to transform our economy. The core idea is simple: technological progress like Gen AI drives productivity gains, which ultimately benefits everyone by lowering costs.

Accenture predicts that adoption of generative AI at scale could unlock over $10 trillion in additional economic value globally by 2038. Similarly, PwC estimates that AI could boost the global economy by $15.7 trillion by 2030 through productivity enhancements alone.

Now, you'd think with such massive potential, everyone would be jumping on the AI bandwagon. But it's not that simple. History tells us that even when innovation can make things faster, better, and cheaper, there are often lots of roadblocks - especially from those whose jobs are on the line.

Upton Sinclair, an American writer and activist, pointed this out back in 1935 when he wrote in his novel "I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked":

"It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!"

Sinclair, a journalist and social activist, was referring to the challenge of rallying support for his End Poverty in California (EPIC) platform during the Great Depression, which threatened the interests of entrenched business and political elites.

His insight rings just as true for today's AI revolution. Incumbents in many industries, from professional licensing groups to unions, will likely resist and try to influence the adoption of new technology that could disrupt their livelihoods.

In this article, we'll explore the challenges and potential roadblocks to widespread AI adoption. First, we'll examine how professional organizations, such as the American Medical Association, may resist or shape the implementation of AI to protect their members' interests. Next, we'll delve into the role of unions in negotiating the terms of AI adoption, using the Writers Guild of America strike as a recent example. Finally, we'll consider the challenges faced by the majority of workers who don't have the protections of unions or licensing organizations as AI continues to transform various industries.

Professional Organizations: Balancing Innovation and Prudence

Reducing costs and increasing access to healthcare is a widely shared goal, right? But before we can even consider the impact of AI in this area, it's important to look at the current landscape and the dynamics at play.

As healthcare costs continue to rise, there have been efforts to enable registered nurses (RNs) and physician assistants (PAs) to take on certain tasks traditionally performed solely by doctors. The rationale is simple: allowing RNs and PAs to handle these tasks can improve access to care, particularly in underserved areas or during physician shortages. Moreover, utilizing RNs and PAs for these duties can be more cost-effective than relying exclusively on physicians, potentially reducing healthcare costs for patients and the system as a whole. Sounds like a win-win, right?

Not so fast, says the American Medical Association (AMA). The organization has aggressively lobbied against expanding nurse responsibilities, labeling it dangerous "scope creep" and touting successful efforts blocking such initiatives across multiple states. The AMA contends that allowing "scope creep" could undermine the physician-led, team-based model of care, which they believe is essential for providing high-quality, coordinated care. They also argue that expanding RN and PA roles could blur professional lines and confuse patients about their healthcare providers' qualifications and responsibilities.

So, what does this mean for AI in medical care? The FDA already categorizes medical devices into Class I, II, or III based on their risk, with increasing regulations and oversight for higher classes. Class I devices require minimal approval, while Class III devices undergo extensive review. Expect physician groups to lobby intensively for AI-powered diagnostic or treatment systems classified as Class II or III devices, requiring physician supervision and restricting their autonomy. Citing risks of liability or accuracy, the goal will be preserving doctors' role in oversight.

Physicians aren't the only occupation with a strong licensing body. Professional Engineers (PEs), architects, surveyors, Certified Public Accountants (CPAs), financial advisors and planners, insurance agents and brokers, real estate agents and brokers, and lawyers all have licensing groups that can use the power of licensing to restrict the ability of new technology to change the way their profession operates.

While these professional organizations play a vital role in maintaining standards and protecting public safety, their influence can also slow the adoption of beneficial innovations. The case of prudence can be a good way to shape how technology gets adopted, ensuring that new tools are thoroughly vetted and responsibly deployed. However, this caution can also impede the swift and large-scale adoption of technology, even when it offers benefits.

Related:

New Wave, Familiar Undertow: How Incumbents Will Resist AI Like Past Disruptions

“Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome.” Charlie Munger Come April, Americans are ensnared in the thorny thicket of taxes. Amidst the scramble of calculations and paperwork, many pause to wonder: with the advanced infrastructure in the US, why are we still manually computing our taxes? After all, doesn’t the IRS already have most of this i…

Unions: Navigating the Tension Between Automation and Livelihood

Just as professional licensing organizations can resist changes, unions also play a role in shaping the adoption of new technologies in the workplace. However, the dynamics are a bit different.

At first glance, it might seem that unions don't have the leverage to fight against technology adoption. Under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), employers and unions are required to negotiate over topics that directly impact workers (wages, hours, etc). Technology is considered "managerial prerogative" and employers are not required to negotiate.

The "Battle of Wapping" in 1986 exemplifies the challenges unions face when confronting technological change. Rupert Murdoch, the media mogul and owner of News International (now News UK), sought to introduce technological innovations that would put 90% of the old-fashioned typesetters out of work. In an attempt to facilitate the transition, the company offered redundancy payments ranging from £2,000 to £30,000 to each typesetter willing to quit their old jobs. However, the union rejected the offer, and its 6,000+ members at Murdoch's papers went on strike.

Unbeknownst to the striking workers, News International had secretly built and equipped a new, technologically advanced printing plant in the London district of Wapping. This new facility could print the paper with just 670 employees, a fraction of the workforce required at the old plant. On January 24, 1986, Murdoch covertly moved the production of his newspapers from the traditional print unions' stronghold on Fleet Street to the Wapping plant. This strategic move allowed Murdoch to dismiss around 6,000 employees, including hot-metal typesetters, compositors, and other print workers from the old plant, effectively breaking the power of the print unions.

In a more recent example, the Writers Guild of America (WGA) faced a similar challenge with the rise of generative AI in 2023. Initially, when the WGA leadership began setting priorities for the negotiation of the next three-year contract, the issue of generative AI was not even on the list. The union's priorities centered on traditional issues such as minimum payments, residuals, and staffing size. However, by early 2023, as awareness of ChatGPT's capabilities spread, the WGA's stance on AI changed.

During negotiations, the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) refused to negotiate on AI, leading to a breakdown in talks. Nearly unanimously, guild members voted to authorize a strike, which began on May 2 and lasted for 148 days, becoming the second-longest strike in the WGA's history. The resulting contract, heralded as a major victory for the writers, explicitly spells out that AI is not itself a writer competing with humans, but rather a tool for writers' beneficial use. The regulations specify that AI should complement the work of writers instead of replacing them, and the contract permits studios and writers to use generative AI under specific circumstances, with guardrails that protect writers' employment, credit, and creative control, while also protecting the studios' copyright.

The WGA strike demonstrates that unions can successfully negotiate the terms of AI adoption in their industries, even if they don't have the same legal leverage as they do with traditional bargaining subjects.

What About the Rest of Us?

The examples we've covered so far in this article - professional licensing organizations and unions - may give the impression that the U.S. workforce has leverage when it comes to shaping the adoption of new technologies like AI. However, this is not the case.

In fact, just 10% of the U.S. workforce belonged to unions in 2023, down from 10.1% in 2022. That's the lowest in Labor Department records dating back to 1983. As for jobs managed by licensing organizations, it's less easy to estimate the numbers. There are about 1.3 million lawyers, 1.1 million doctors, and 930,000 professional engineers. Let's call it another 14 million employees or 20% of the workforce.

The rest of us - the vast majority - work independent of those organizations. As I look back on my own career in startups, I've held roles like software developer, quality assurance tester, product manager, marketer, content creator, community moderator, ad trafficker, account manager, HR representative, and bookkeeper. None of these positions required licensing. Thank goodness, because no one should have licensed me to do many of those gigs - I was out of my depth in many of those domains! But that's also what made the startup possible. The ability to wear many hats and learn on the job is a hallmark of the startup world, and it's a reality for many of us across industries.

It's important to note that this isn't an argument for or against unions or licensing organizations. They play a vital role in protecting workers' rights and ensuring professional standards. However, it's crucial to recognize that most jobs don't require licensing or have union representation, which means that the majority of workers don't have the same level of influence when it comes to shaping the adoption of new technologies like AI.

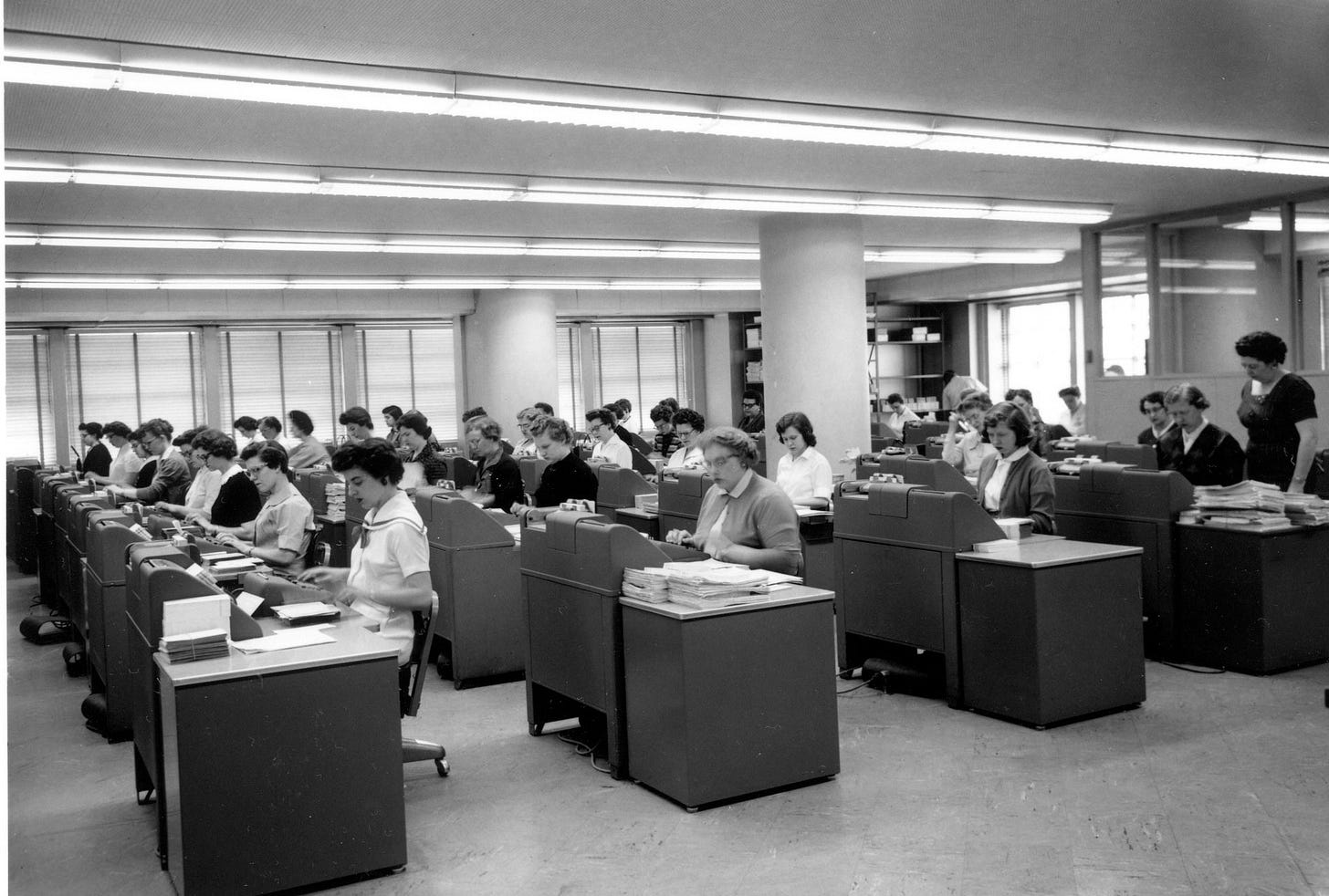

Moreover, roles like these often morph and/or dwindle with technological advancements. Consider the typist pool in companies before the era of personal computers. In 1960, for example, one in ten Americans worked as a secretary, stenographer, or typist. These roles were critical to the functioning of corporate and governmental bureaucracy. In 1971, the New York Times reported on how 600 people were stuck in jail because there were not enough typists to type out the dictated probation reports. But as technology advanced, this profession has become a thing of the past.

As AI continues to evolve and permeate various industries, it's likely that we'll see similar shifts in the job market. Some roles may become obsolete, while others will transform and adapt. For the majority of workers who don't have the protections of unions or licensing organizations, navigating these changes will be a challenge.