Reinvent or Relinquish: You Can't Sell Horseshoes to People Who Don't Own Horses

Those spellbound by AI's potential to expand their wallets may miss how it may empty their customers' wallets - a myopia that has drained the fortunes of many a once-proud enterprise.

If you're just joining us, this series follows the journey of a brilliant product manager, you. You've steered the product strategy of a company, Warehouse Software Inc, through 3 decades of technology disruptions. But in 2026, the company faces its biggest test yet - the ascendance of AI. The CEO has called an offsite, and the team is grappling with the implication of AI and how the flagship product, Warehouse Tracker, should respond to the change.

Here are links to the rest of the series:

Moments That Modernized: Four Decades of Tech's Tectonic Shifts

The Economics of Abundance: What Do You Charge When Software is Free to Produce?

The group reconvenes after lunch, buzzing with ideas but also uncertainty. The VP of Sales, a pragmatic leader focused on tangible results, speaks impatiently. She's tired of being at the off-site.

"We've diagnosed the situation," she says bluntly. "It's a disruption. Innovator's dilemma, the S-curve of product innovation, etc. But how do we transition from identifying threats to taking action? We need to do more than just congratulate ourselves for 'spotting trends.' "

You smile. You love her directness. "It is a disruption," you say. "But it's different from past ones we've weathered. Do you all remember when mobile devices transformed how our customers worked?"

Heads nod as people recall those days. (Read episode 1 for a recap)

Ask not what disruption does for you. Ask what it does for your customer

You continue, "When mobile devices became widely available, our customers equipped their warehouse staff with mobile phones and tapped the built-in cameras. We scrambled to build mobile interfaces and apps, rethinking how our software should function in this new environment. Though difficult, the rise of mobile ultimately expanded our market. There were more seats sold and more end users."

The CMO acknowledged the benefits but pointed out the challenges. "We also contended with mobile-first warehouse apps trying to poach our customers by portraying our software as outdated. And we coped with the lower prices they offered."

You nod. "True, but for our software category, mobile was a net gain."

The CTO offered another example. "Transitioning to the cloud was similar. It lowered costs to deliver our software, we traded sysadmins for DevOps teams. But it also meant new competition because there were lower barriers to entering the market. Even though prices dropped, the market grew as more warehouses pursued automation."

The group was fully engaged. "But AI's impact could be more like the rise of digital cameras," you say. Eyes narrowed and followed as you walked to the whiteboard.

One-Hour Photo Finish: The Race Film Couldn't Win

"Back in 1996, when I started at Warehouse Software, I bought the Kodak DC25 - the first digital camera sold to consumers at scale," you say. "But it was a toy. At 493 x 373 pixels, storing 14 photos, it couldn't replace my film camera."

You recall what film photography entailed: buying rolls of Kodak Gold or Fuji Superia, shooting 24 or 36 photos, then dropping off the film at the lab for developing, waiting days for the prints - or paying extra for one-hour service at your local Wolf Camera or Ritz Camera shop.

You gesture as if presenting an old-time photo mart. "Now picture Noritsu, a Japanese photo mini-lab company, in 1996. Their innovation enabled one-hour photo development at grocery stores, drug stores, and even malls. Wolf Camera, Fox Photo, Ritz Camera - they were everywhere."

"I remember those stores," someone says fondly. Others chime in with memories of loved camera shops now gone.

You continue, "Noritsu's largest mini-labs could process 3,000 film rolls per hour. They were in Costco, Sam's Club, meeting demand for ever-faster service. Kodak's FunSaver disposable cameras were available for $5-$10, and it meant that anyone could shoot a roll of film and drop off the camera for quick 4x6 prints in under an hour. The future looked bright for Noritsu and one-hour labs, fueled by a boom in single-use cameras. Kodak sold tens of millions of FunSavers, Sunny Savers, FlashSavers, and more each year."

You pause, letting the scene sink in. "But looking ahead, the signs were clear. The digital photo value chain did not need mini-labs. No matter how much better the mini-labs got, their customers were dying"

The CTO realizes where this is headed. He chimes in, "No point building a 10-minute photo lab if no one is developing film."

Into the silence, the VP of Sales speaks the brutal truth: "You can't sell horseshoes to people who don't own horses."

The mood turns somber as people realize the implications. Despite its success in the ’80s and ’90s, the mass transition from film to digital decimated companies in the old value chain. Like Noritsu, they were blindsided by new technology that made their offerings obsolete almost overnight.

TAMageddon: For Whom the Market Tolls

The board member stands and paces, brow furrowed. "We invest in growing markets, not shrinking ones," he says.

"Software provides automation, which boosts customer productivity. But if customers disappear, so will your market."

He gestures as if presenting a thought experiment. "Take data analysts, for example. Initially, tools like a SQL Copilot help analysts work faster, so you need fewer analysts. But eventually, business users get their own AI ‘copilots’ to build reports. You might not need human analysts at all. If you're selling software to data teams and assume data jobs will keep growing, you're in for a surprise. The same goes for writers, illustrators, even software developers. If AI automates your customers' jobs, you'll be in trouble."

The CFO looks up from their laptop. "Goldman Sachs says AI could automate 300 million jobs - two-thirds of today's jobs. If you're selling to any of those you might be in trouble?"

The VP of Sales grins. "So - are we selling horseshoes, and have we hit peak horse?"

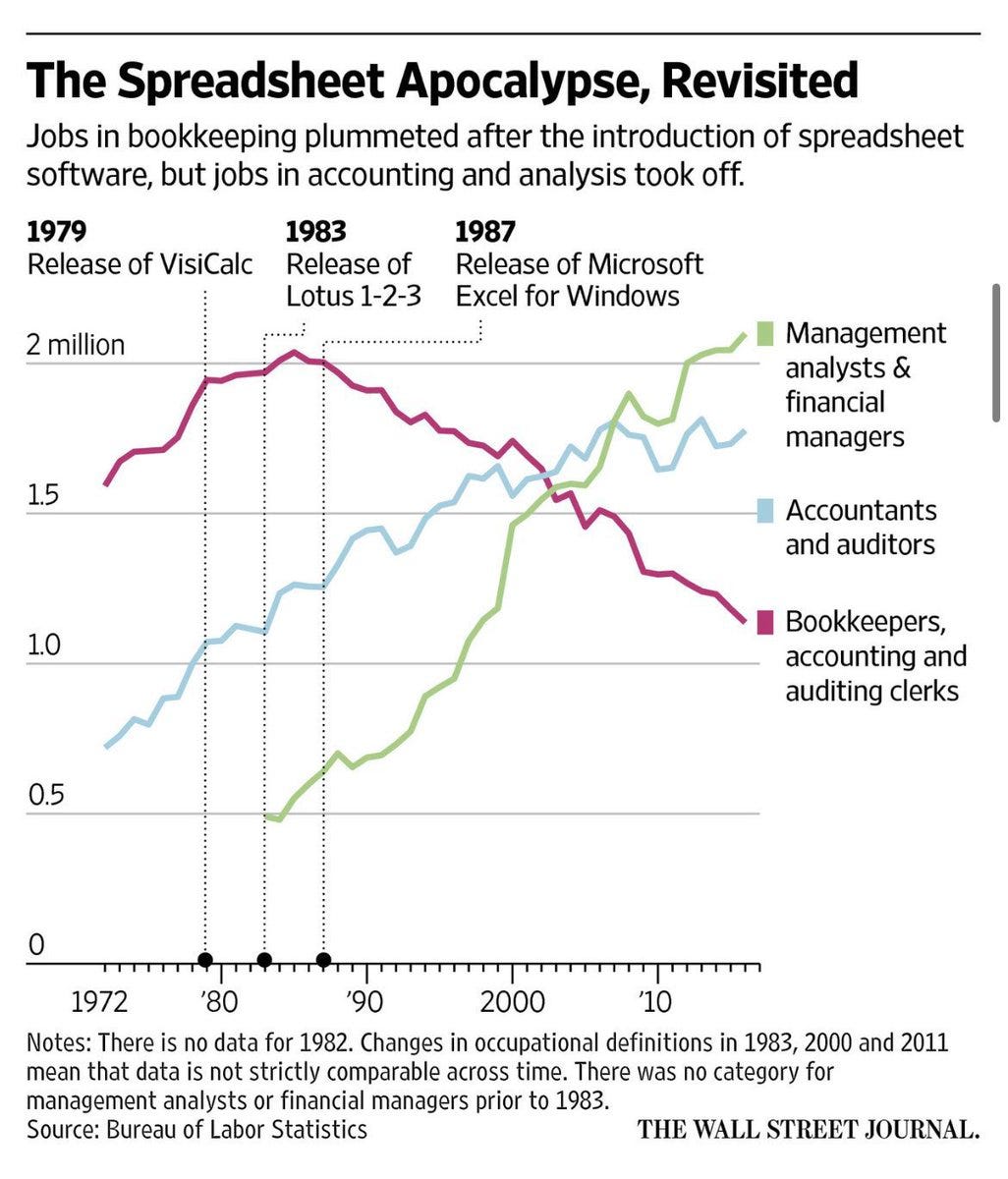

The board member raises a hand. "Slow down. Automation doesn't necessarily mean job losses. It could increase demand for certain roles. When spreadsheets emerged, accountant jobs actually grew."

Transformation is the Only Option

The CEO steps forward, surveying the room with a wry smile. The atmosphere buzzes with nervous energy after hours of intense discussion.

"We have three more sessions before this 'offsite' ends," he says, "or this newsletter will turn into 'War and Peace'!"

A chuckle rolls through the crowd, releasing some tension.

"In our next session, we'll analyze the warehouse value chain to see how AI could transform our customers' world," he continues. "Then we'll explore the tech enabling on-demand software and how we could use it. Finally, we'll define next steps to build our future"

"Today's talks were 'very necessary,' if not always fun," he says. "But we now see what's at stake. Our industry's 'peak horse' moment may be here already…so we'd better 'giddyup'!"

There are groans and chuckles at his puns. But nods of agreement, too.

As people head to dinner, the board member pulls you aside. "What happened to Noritsu, in the end?" he asks.

You shrug. "The sources I found weren't definitive, but seem to say that Noritsu's revenues peaked at over $1.4 billion in 1996, then dropped 90% to $126 million by 2008."

"Falling photofinishing equipment sales fueled the decline, as that market nearly disappeared. Noritsu's fate followed the industry they led."

The board member nods, gazing into the distance. "Funny thing is, the first consumer inkjet photo printer also emerged in 1996. We must figure out how to be HP or Canon - not Noritsu." He grins wryly. "No pressure, right?"

You laugh. "Yeah, this is 'floor is lava' - the business version!"