All In on the Cloud, All In on the Device

Why the companies spending $405 billion on cloud infrastructure are simultaneously betting on local AI

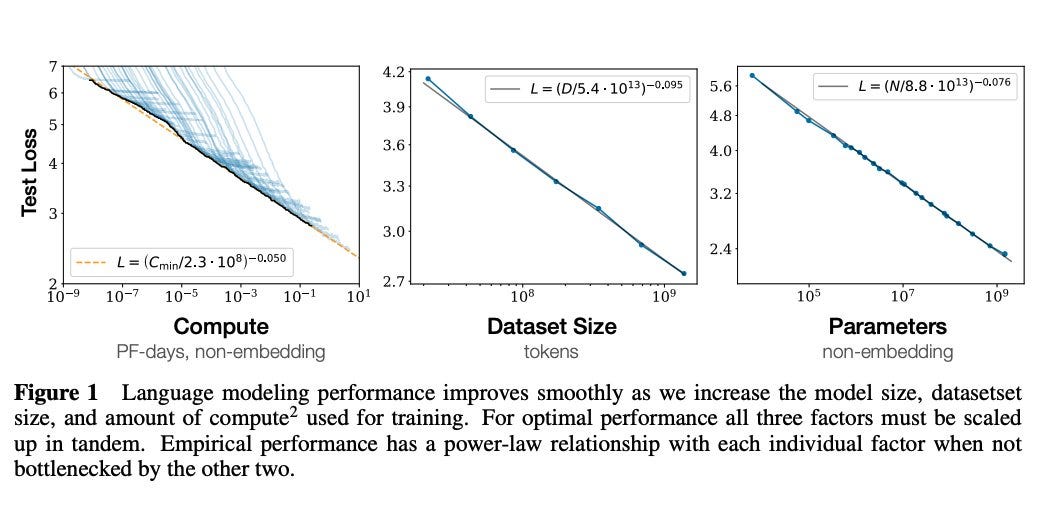

In January 2020, a team of researchers at OpenAI published a paper that would reshape the AI industry. The paper had an unassuming title—“Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models”—but its findings were anything but modest. Jared Kaplan and his colleagues had discovered something that looked almost too good to be true: a formula.

They found that the relationship between model size, training data, and performance wasn’t random or unpredictable—it followed clean mathematical curves. Double the parameters, and performance improved by a predictable amount. Add more training data, same result. Pour in more compute, watch the metrics climb. The curves held across seven orders of magnitude.

This observation became a roadmap.

Before this paper, building AI felt like alchemy—part science, part guesswork, with occasional breakthroughs. After it, the path forward seemed almost mechanical. You didn’t need a brilliant new algorithm. You didn’t need a conceptual breakthrough. You just needed to go bigger.

The paper arrived at exactly the right moment. Rich Sutton, one of the founding figures of reinforcement learning, had published an essay the year before called “The Bitter Lesson.” His argument was blunt: for seventy years, researchers had tried to build intelligence by encoding human knowledge into systems. They always failed. What actually worked? Throwing more compute at simpler methods. “The biggest lesson that can be read from 70 years of AI research,” Sutton wrote, “is that general methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin.”

Kaplan’s scaling laws gave that lesson a formula. And the industry took notice.

What followed was the most dramatic expansion in AI history. GPT-2 had 1.5 billion parameters. GPT-3, released just five months after Kaplan’s paper, had 175 billion—over a hundred times larger—and GPT-4, released in 2023, reportedly exceeded a trillion. Each generation proved the formula worked: bigger models wrote better prose, solved harder problems, passed more exams.

If bigger always meant better, then the path to artificial general intelligence was simply a matter of scale. Build larger models. Train on more data. Construct bigger data centers.

And so the money started flowing. Not millions. Not billions. Hundreds of billions.

In 2025, the major tech companies spent over $405 billion on AI infrastructure. Amazon alone invested $125 billion. Google, Microsoft, Meta—each poured tens of billions into facilities that draw gigawatts of power, enough to run small cities. The International Energy Agency projects that data center energy consumption will more than double by 2030, eventually exceeding the power demands of aluminum, steel, and cement production combined.

This is what conviction looks like. The industry went all in on a single thesis: scale is all you need.

But what if the formula is breaking down?

The Scaling Wall

In December 2025, Sara Hooker published a paper with a provocative title: “On the Slow Death of Scaling.” Hooker isn’t a contrarian blogger or an industry outsider. She led research at Cohere For AI before co-founding Adaption Labs. Her argument wasn’t that scaling had never worked—it was that its returns were collapsing.

“If you double compute size,” Hooker wrote, “you get... a measly two percentage points of performance.” The relationship between training compute and capability had become “uncertain and rapidly changing.” The easy gains were gone, and the clean curves from Kaplan’s paper were bending.

But she’s not alone. Ilya Sutskever, who co-founded OpenAI and led the research that created GPT, described a similar shift in a recent podcast interview: “From 2020 to 2025, it was the age of scaling. People say, ‘This is amazing. You’ve got to scale more. Keep scaling.’ The one word: scaling. But now the scale is so big... it’s back to the age of research again.”

The recipe that worked—mix compute with data in a neural net, scale it up—gave predictable results. Companies loved it. A low-risk way to invest billions. But Sutskever sees the end approaching: pre-training will run out of data, and what comes next might require different approaches, new algorithms, something beyond just making models bigger.

Not everyone agrees. Epoch AI, a research group focused on forecasting AI progress, published projections arguing that scaling continues well past 2030. They point to recent models that show continued improvements, and argue that synthetic data could solve the data bottleneck before it ever materializes.

So there’s genuine uncertainty about whether the infrastructure bet rests on a law that’s breaking or one that still holds. But nobody wants to let off the gas—if scaling continues and you pulled back, you’ve ceded the future to your competitors. The cost of being wrong is existential.

Small as the New Big

While experts debate whether scaling will continue, something else is happening that changes the deployment economics entirely: small models are getting shockingly good.

Between November 2022 and October 2024, the cost of running a GPT-3.5-level model dropped 280-fold—from $20 per million tokens to $0.07—while energy efficiency improved 40% annually. And the performance gap between small and large models is closing fast.

Aya at 8 billion parameters beats BLOOM at 176 billion—4.5% of the size, better results—and Llama 3 at 8 billion competes with models twenty times larger. Not on every task. But on enough tasks to matter.

How is this possible?

When you train a large model, you end up with massive over-parameterization. The network creates millions of redundant weights—duplicates and correlations storing the same information in multiple ways. This redundancy is how the model learns, exploring different pathways to understanding.

But once training is complete, all that redundancy becomes dead weight. Through a process called distillation, you can compress the knowledge into a much smaller model—a large “teacher” training a smaller “student,” transferring intelligence to a leaner architecture. The student learns from the teacher’s full probability distributions, not just hard answers, preserving sophisticated reasoning in a fraction of the size.

This reveals something important: we need massive scale to discover intelligence, but we don’t need it to deploy what was discovered. The knowledge locked inside a trillion-parameter model, learned over months of compute, can be distilled into something that fits in your pocket.

Research from NVIDIA shows that 40-60% of agent workloads—the everyday tasks people actually do—can be handled by specialized small models.

The industry was built around one assumption: if you need gigawatt data centers to train models, you need them to run models too. But what if training and deployment follow completely different curves—the breakthrough requiring massive scale, but delivery not requiring it at all?

The Hedge

The companies spending billions on gigawatt data centers are also quietly building for a world where those data centers matter less. They’re not choosing between scaling and small models. They’re betting on both.

When you have hundreds of billions in resources, you don’t pick sides—you ensure you win either way.

Start with Google. They built Gemini to compete with GPT-4 in the cloud, then released Gemini Nano—a version that runs entirely on your phone—and followed it with the Gemma family: models ranging from 1 billion to 27 billion parameters, specifically designed for local hardware. The smallest version runs in Chrome itself, processing your data without it ever leaving your browser.

Microsoft spent $13 billion partnering with OpenAI and is pouring billions more into Azure infrastructure to dominate cloud AI. But they also built the Phi family—small models with 3.8 to 14 billion parameters designed to run on laptops.

Apple went all-in on local from the start. Every Mac ships with unified memory architecture that turns your laptop’s RAM into AI memory—an M4 Max with 128GB runs 70-billion-parameter models that would normally require a server rack. The pitch is explicit: your data stays on your device, and the cloud only gets called for the hardest problems.

Then there’s the hardware mandate that almost nobody noticed. Microsoft’s Copilot+ PC specification requires every certified device to include a Neural Processing Unit—a chip dedicated to running AI locally. Google’s next generation of Chromebooks will require NPUs, and Apple already ships them in every device.

The entire PC industry is being quietly restructured around local AI.

And then there’s NVIDIA—the company worth over $3 trillion selling chips to data centers, whose H100 and H200 GPUs power the vast majority of AI training runs.

But NVIDIA is also building chips for your laptop. The N1 and N1X combine their Blackwell GPU architecture with ARM processors for local AI inference, and at CES they unveiled the DGX Spark—a desktop computer that runs 200-billion-parameter models locally. Lenovo is already preparing consumer laptops around these chips.

If local AI takes over, NVIDIA doesn’t lose—they become bigger than Intel ever was. Intel at its peak sold CPUs to every PC. NVIDIA could sell AI chips to every PC and every data center.

When you’re worth trillions, you don’t pick a side—you place chips on both sides of the table. If cloud AI dominates, you win. If local AI dominates, you win. No need to bet on just one outcome.

What If the Ratio Is Different?

Right now, the split between cloud and local AI is essentially 99 to 1. Nearly every AI interaction happens in a data center, and the only people running models locally are tinkerers who know how to install Ollama or run Llama.cpp from the command line.

But what happens when local AI is baked into every operating system?

When every Windows laptop ships with an NPU and Phi models built in. When every Chromebook has Gemini Nano running in the browser. When every Mac can run 70-billion-parameter models without connecting to the internet—and the default experience becomes local-first, with the cloud reserved for the hardest 10% of problems.

What does the ratio become then? 70-30? 50-50?

If inference shifts even partially local, the economics of the industry change. Training will still require massive scale—giant models, giant data centers—but the intelligence those facilities produce could end up running on the laptop in front of you.

The data centers don’t become useless. But maybe we don’t need as many gigawatt facilities as we’re building for. Maybe the future isn’t millions of people hitting cloud APIs billions of times a day. Maybe it’s millions of people running small local models that only reach out to the cloud when they’re genuinely stuck.

The companies placing the biggest bets seem to think this is plausible. They’re building for both futures because they can afford to. When you’re worth trillions, you don’t pick a side—you make sure you profit regardless of which world arrives.

And if you’ve been in tech long enough, this probably feels familiar.

Mainframes gave way to personal computers, which gave way to web apps on servers, which gave way to the cloud—and then mobile apps pulled computing back to the device. Now AI is starting in the cloud, and the pendulum is already swinging back toward local.

Thin client, thick client, thin client, thick client—the pattern never changes. The only difference this time is the scale of the bet, and the fact that the smart money isn’t choosing sides.

They’re betting on the pendulum itself.